Designed by Hungarian-born architect Erno Goldfinger in 1963, Balfron Tower has become a global icon of brutalist architecture.

Last week I took off down to Balfron to take some photos. Although slightly smaller than its younger sister, Trellick, standing 26 storeys above East London, Balfron's harsh concrete was visible for miles.

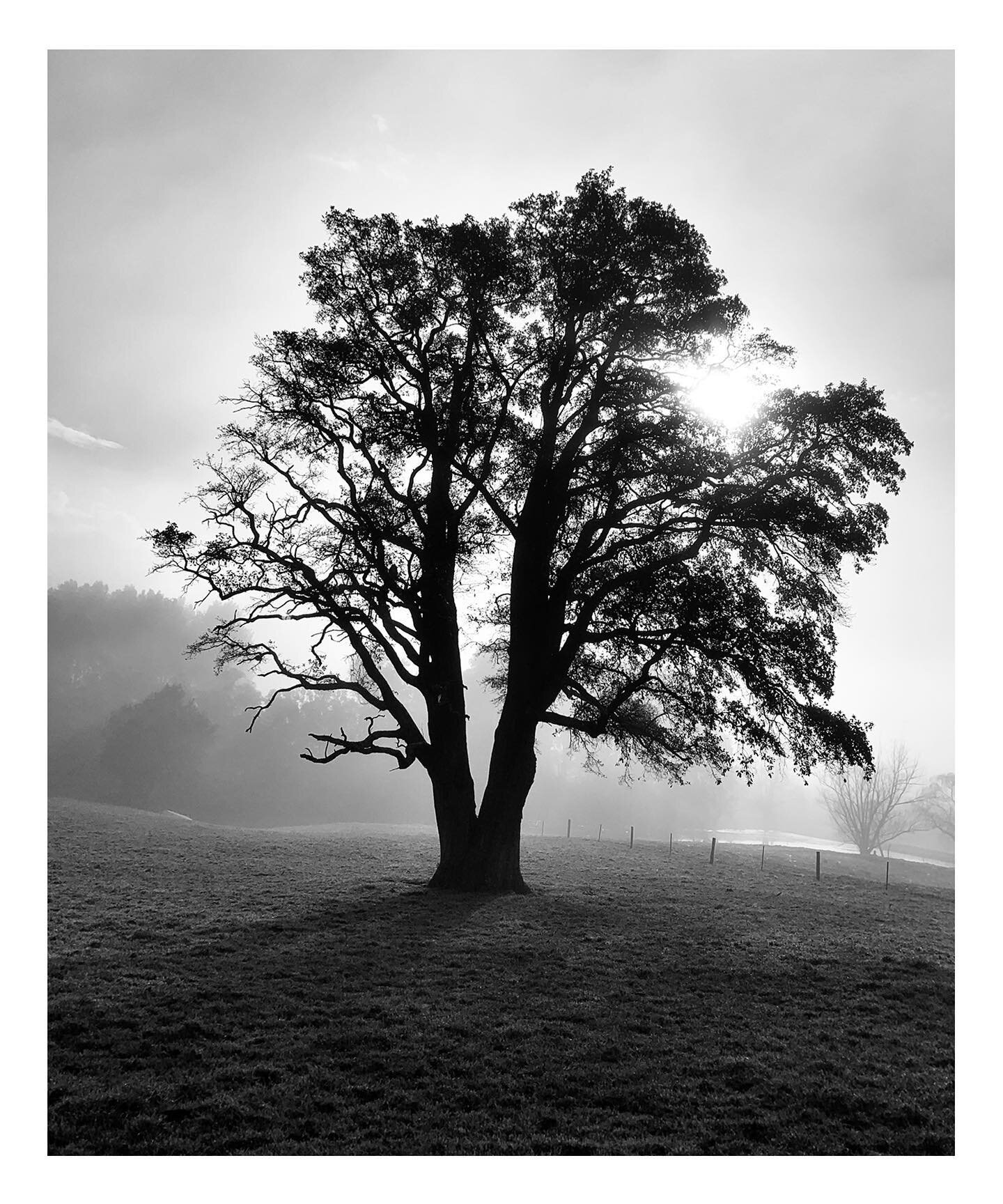

Walking towards the base of the building, the facade overshadowed me like the sheer of a cliff face. But as the building caught glimmers of the morning sunlight through the patchy clouds above, I became very aware of the elegant sophistication of Goldfinger’s design.

Stood taking photos of the towering monolith above, a man yelled, “what’s the intrigue!?” Sensing he was a pissed off resident, I gave him a simple answer, hoping he would move on. Staunchly walking towards me, he asked again, “what is the intrigue?”

Realising that this guy wasn’t about to just walk away I decided to open up explain to him exactly why I was there. I told him of my interest in Erno Goldfinger’s architecture and why I wanted to take photos of this building in particular.

It didn’t take long before the man’s tone of voice lifted, and his demeanor calmed. Suddenly all he wanted to do was tell me of his love for Balfron. As it turns out, he’d lived in the building for 25 years and was now the last social tenant before its sale to the private sector.

He told me about the ensuing court case for his eviction, which was bound to come to close in the following weeks. The volume of his words increase as he explained his frustration at the powers and processes above him, this clearly wasn't the first time he'd told someone his story.

For over 50 years Balfron had housed hundreds of families across 146 affordable housing flats. Now, 145 homes sat empty, and he was the last man standing.

“You wanna come check it out from the inside?” he asked.

Minutes later we were sneaking behind security and shuffling into the building’s stainless steel elevator. Creaking up to level 26, and stepping out onto the grey, concrete flooring, I was immediately overwhelmed by smells of booze and urine. Fortunately for us the breeze from the awning-hinged windows helped to disperse the smell through the corridors.

Peering through the horizontal pattern of windows, the view from the top was incredible: Poplar sat quietly below, the city skyline loomed in distance.

As I walked down the long corridors I imagined Erno’s ambition for ‘streets in the sky’, where working class neighbours would socialise and kids would play games. It was too bad, bottles of half drunken bottles of beer and empty NOS canisters now lined the passageways.

After sometime upstairs, it was a relief to break back into the autumn sunlight. I wondered if I could ever live in a dark, concrete tower like this one. For while I could understand Erno’s ambitions, I could also appreciate where his design concepts had failed.

In fact, when I first arrived in the UK, I thought brutalist buildings were disgusting. Having grown up in sunny Australia where there's an abundance of low-rise bungalow-style architecture and spacious streetscapes, I often wondered why London’s huge concrete 'ghettos' hadn’t been ripped down and replaced with something more attractive. But over the years, and after some reading, I began to appreciate the ethos behind their design.

Mainly a reaction to the housing crisis following World War II, this form of architecture attempted to help London’s homelessness by creating large, affordable buildings within accessible inner city areas. While in reality these concepts didn't always work, the ethos - at least - was admirable.

Balfron's last remaining social tenant is likely to be removed by force in the coming weeks. With few places to go, he told me he will likely be pushed outside of London altogether.

In cities across the world, a lack of affordable housing is forcing young people and those on low incomes to look for housing alternatives. Many are moving out of the cities that they love, whilst others are feeling the impacts of living in a 'rental trap'.

As the last social tenant is forced-out of one of the world's most famous brutalist buildings, I wonder what Erno Goldfinger thinks of his building, and architecture, today? Would he be ashamed that we now completely ignore the socialist principles of the brutalist era?

I would never suggest that contemporary designers should copy Balfron Tower, or even brutalism, as a concept. But the ambition of its developers, and their architectural boldness, would be something to emulate.

Photographs by Dan Young & Tom Oliver Payne.