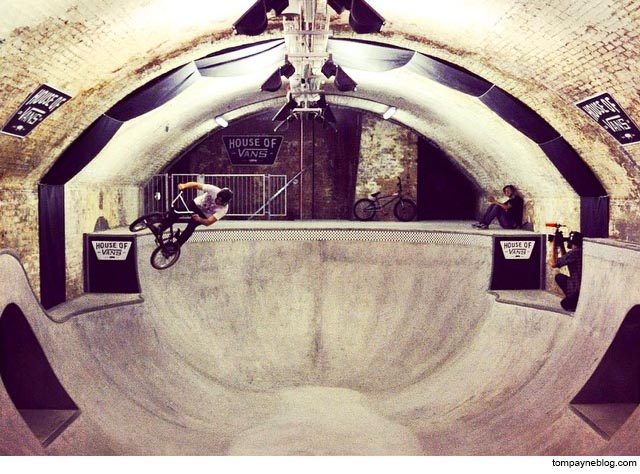

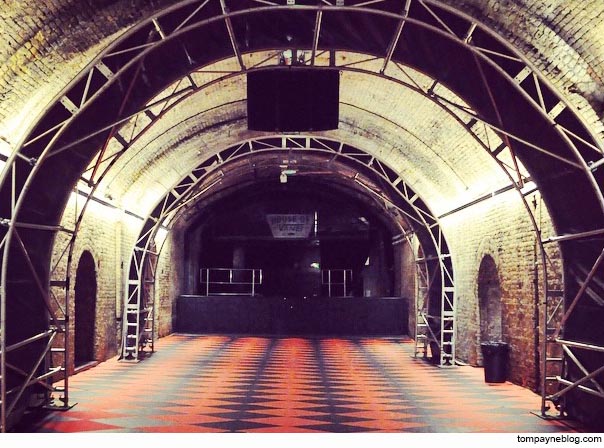

Often a city's ugliest buildings are its most controversial.

The Fred Wigg and John Walsh Towers in London’s were loaded up with missile launchers during the London olympics - making the tenants inside a potential target. Now, at the forefront of the gentrifying east end, it’s likely that the towers will soon be demolished and redeveloped. The tenants, however, still don't know how long until they will be 'decanted'.

The speed at which this city changes constantly amazes me - but unfortunately - affordable housing tenants are too often left in limbo during the development process. I'd love to see these buildings recreated into something beautiful. I'd also love to see space made for existing tenants who have spent decades building a life within the community.

Either way, it looks like these buildings will soon be cleared from London's landscape, or - at least - remade into something new. I made the images below to document their place within amongst the skyline before they're no more.