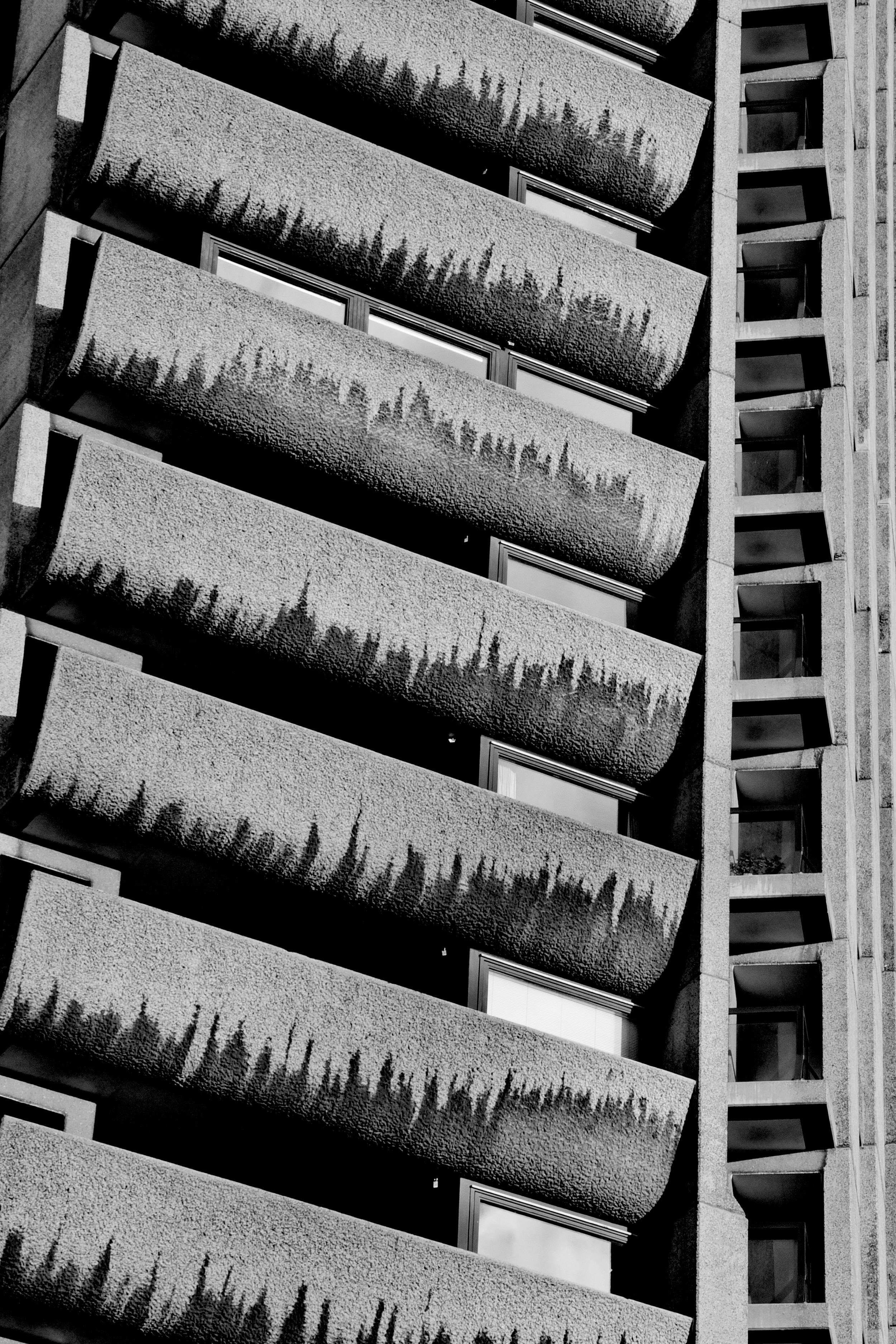

4. Our world will be personalised

Every one of the 7 billion humans on this planet is unique. So why not make objects and environments just as unique as we are?

Last month I met designer Ross Atkin, who is using digital technology to personalise our streets for the blind or less abled. I was super impressed with his work – which is both inspiring and practical. By using technology and data which already exists, Ross’ work can improve the lives of millions.

But as artists Margot Bowman and Marcus Lyall took to the stage on Monday night, I realised that the future of personalisation won’t just stop there. These artists work at the intersection of art and technology, creating bespoke environments which respond to our needs, wants and emotions. Not only can technology help to solve problems, but it can also enhance our day-to-day experiences and pleasure.

As Anders Warming, Head of Design, MINI, showed us how the MINI Vision Vehicle will respond to our emotions through lighting, I started to foresee an urban future which only a few years ago was completely unfathomable.

Objects will no longer just be objects. But just like my smart phone rather than my chunky old Walkman, future belongings will become completely integrated into just about every aspect of my life.

Helping us to move, plan, manage and organise, we create more time to do the all things we love.

Heading along to Monday’s event, I thought I would be checking out some cool technology and design ideas. But I had no idea that the conversation around the future would open my mind to so many interesting insights into the way we might behave, and perceive the world around us in the future.

It made me super excited to see the shape of things to come. I’d love to know your thoughts – what is your ideal future city?

The BMW Group Future Experience, showcasing MINI’s Vision Vehicle is taking place at the Roundhouse in London until Sunday 26th of June. Visit www.mininext100.co.uk or @MINIUK for more information. #MINI #NEXT100

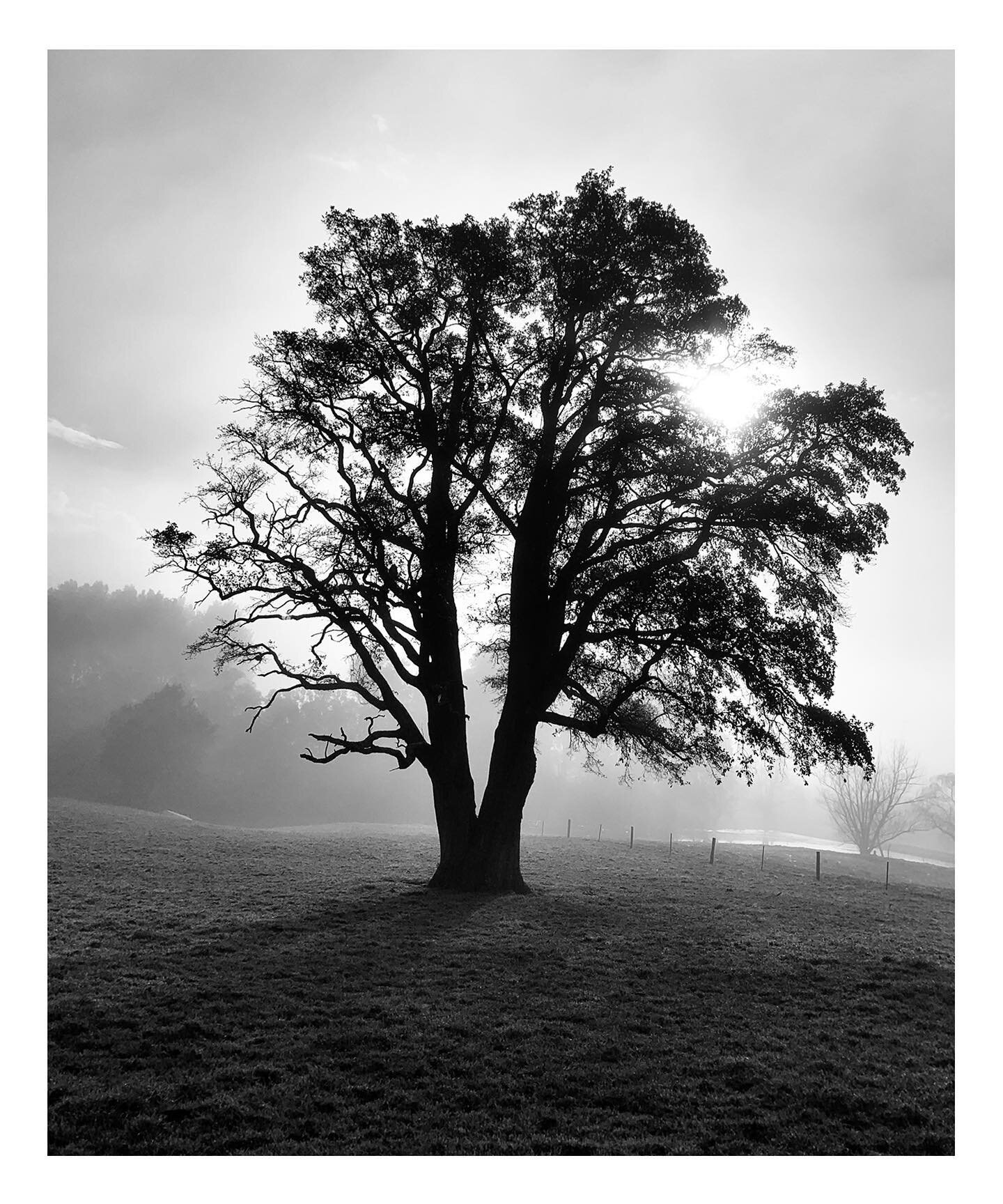

Feature photo: Mark Fischer