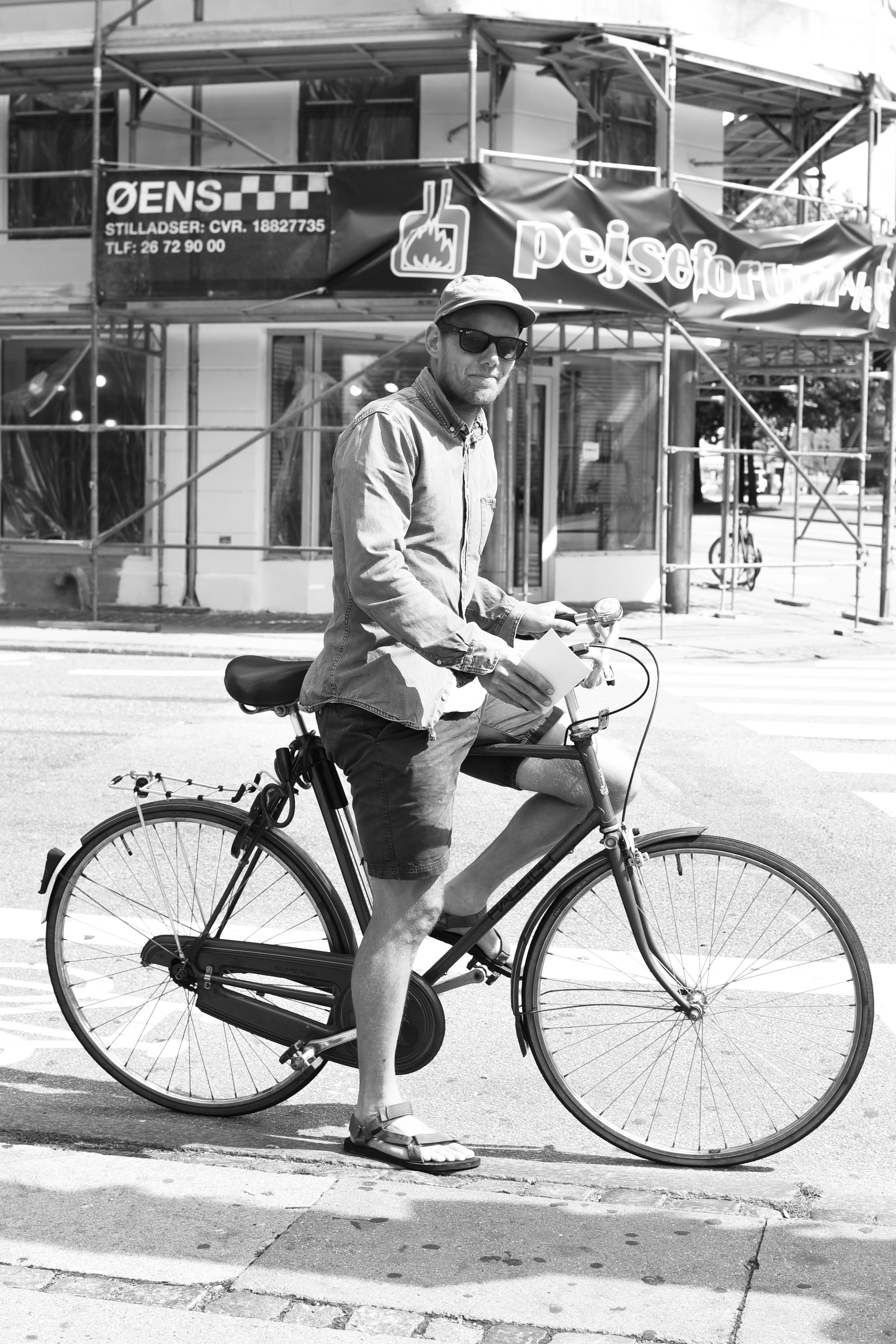

A couple of years ago, I did some research into why London was finding it so difficult to implemented Danish-style infrastructure. After speaking with experts in London, I took off to Copenhagen to experience riding in the city and speak with urban designers and government officials. It was obvious to see how a combination of traffic calming measures and separated bike paths create a city that is vibrant, safe and beautiful.

The research findings were simple: despite copying overseas lingo like ‘Cycle Superhighways’, London doesn’t really try to copy anyone. It tries to do things its own way. New designs try to please everybody, but in doing so, the results don’t please anybody. What we’re left with is a surface-transport mess. It simply doesn’t work for pedestrians, drivers or those on bikes.

This year, I wanted to find a city that is doing things properly. I wanted to find a place that knows how it wants to improve and is quickly making the right changes to get there. The city I found was Vitoria-Gasteiz – the 2012 European Green City winner.

In just ten years Vitoria has completely transformed itself from a car-dominated, polluted city to one of the most pedestrian and bicycle-friendly in Europe (and probably the world). Today over 50% of people walk to get around and 12% of people ride bikes. The number of people driving cars quickly continues to fall. Compare this with 21% people walking and 3% riding bikes in London, and 10% and 1% respectively in New York City.

I took off down to Vitoria to see the city first-hand and meet some of the people making this transformation happen.

Speaking with the Director of the Environmental Studies Centre (CEA), Juan Carlos, I learned why the city embarked upon this rapid transformation. “Just ten years ago, this city had a lot of problems with the car,” Juan told me, “but people knew it shouldn’t be like that, so we begun to think about how we could change it”.

The CEA receives funding from the city government but really only has one task at hand: improve the way the city functions. It independently advises the government on how it can improve, without getting bogged-down with day-to-day administration. This is very different to most other large cities, which leave important research and plan-making to oversized government bodies. With a relatively small team of a few dozen people, its no wonder the CEA quickly and effectively gets work done.

Juan told me that just ten years ago, the city decided to get off its backside and develop a progressive Sustainable Mobility and Public Space Plan. Instead of just looking inward, the team decided to see what other cities were doing to overcome similar problems. In collaboration with the German NGO for sustainability, Verkehrsclub Deutschland (VCD), Vitoria joined the European Biking Cities project. This enabled the city to learn from other urban areas with ambitious cycling policies.

When learning from others, Juan and his team didn’t simply implement three-metre wide bike paths like Danish cities, or turn one-way streets to two-ways, like in American cities. Instead Vitoria copied and pasted intelligently. Successful elements from elsewhere were carefully integrated into the city’s own context and adjusted where necessary.

Vitoria implemented Copenhagen-style bike paths on wide thoroughfares (when it could afford to); it used the ‘superblock’ idea from Barcelona to divert traffic and free up space for pedestrians; and it took greenways design characteristics from the Netherlands to create beautiful and attractive pedestrian environments, where people would actually want to spend time.

The Sustainable Mobility and Public Space Plan was then fully integrated with a new public transport plan. The aim was not to get as many people onto public transport as possible, but rather to get as many people out of cars as possible. Just like the caution surrounding Copenhagen’s new tram network, the city was careful to ensure public transport did not detract from people walking and cycling, but rather only detracted from the number of those driving. This was achieved through careful network design.