Architecture today is generally about making other people big bucks. But Dawson's Heights reminds us of a time when architecture strived to create a better society through design.

Land development today basically works like this: an investor will buy a plot of land, they then hire a developer with a track record of maximising value who will in turn hire architect who knows how to maximise floorspace. For the sake of profit, all parties will hope construction is over and done with as quick as possible, and each bit of land will sell for maximum value. Job done.

But before you call me a pessimist, let me iterate that I don't necessarily think this process is all a bad thing. This process is simply a reaction to our economic market and continual development profits ensures a pipeline of construction and as a result, people - from construction workers to web designers - have jobs.

Unfortunately however, development is too often, too greedy. Due to the speed and aggression of investors and developers, new buildings and spaces often lack quality design or a social conscience. What we are commonly left with is architecture with few zero-to-no societal benefits, doing nothing more than providing the mega-wealthy some real estate to dump their cash. Property has become more concerned with international asset management rather than the provision of housing or the creation of communities.

Clearly, we've seen a recent swing towards capitalist-dominated architecture. But it hasn’t always been this way.

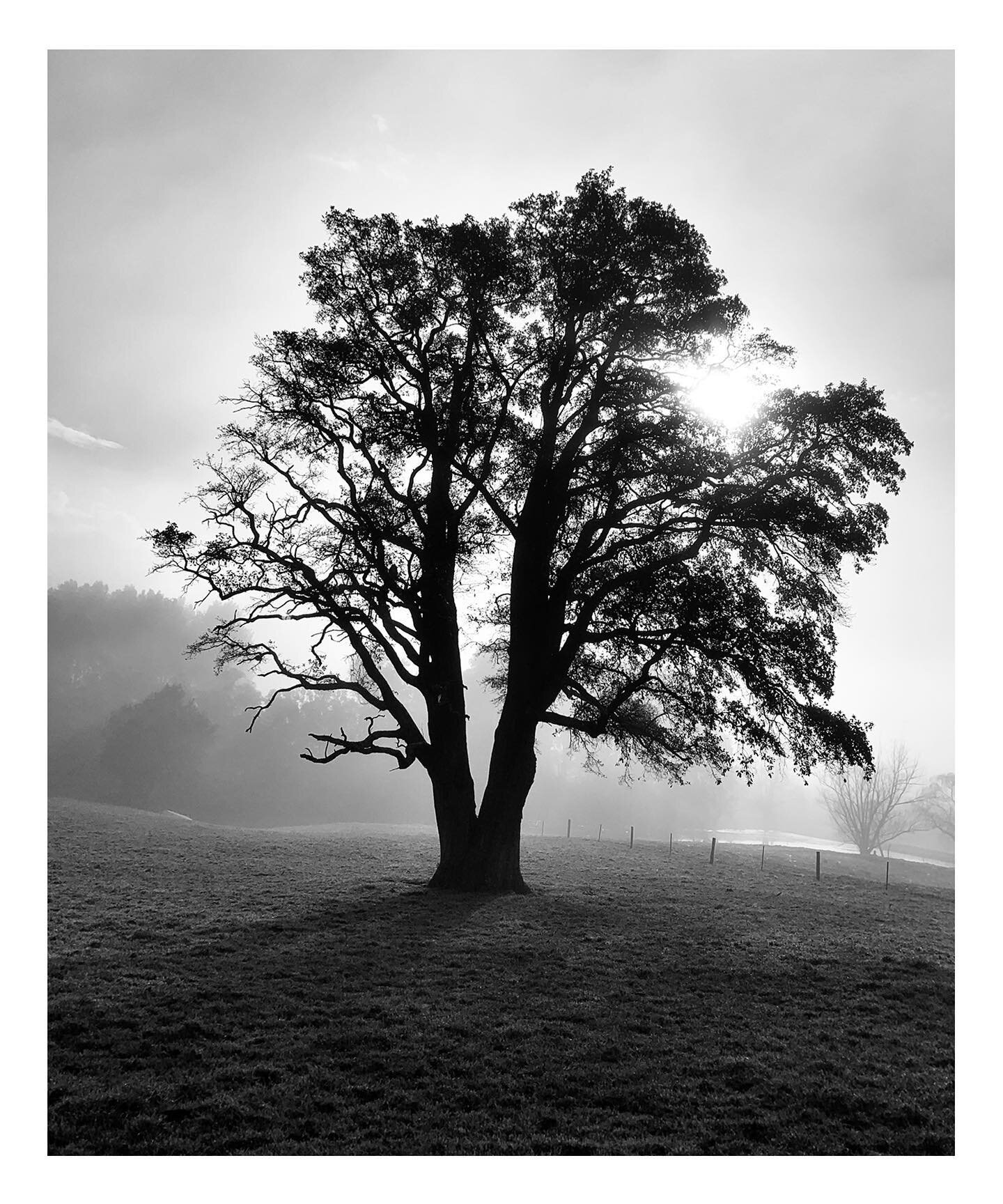

Dawson's Heights' northern block seen from its central public space.

Back in the 60s, architecture in London operated in a very different context. Emerging from the Nazi bombings of World War II, the city was battered and bruised, and thousands were homeless or living in slums. The government took it upon itself to deliver tens of thousands of homes every year through mass redevelopment projects.

While often criticised for their top-down approach to design, no one can argue that they were’t at least ambitious, and at most, incredibly bold.

The Barbican Centre, Trellick Tower and Balfron are some of London’s most famous examples. These brutalist monuments are remnants of a past when - although they didn’t always get it right - architects could at least attempt to solve social problems through creative design.

Not all of the examples from this time were dominating brutalist buildings. Some were smaller incisions in the existing urban fabric such as Golden Lane Estate, and others were modernist creations which boldly - but appropriately - inserted themselves into the remains of pre-war London.

Last week London opened its doors for Open House 2016 and I had the opportunity to check out one of the most impressive examples.

A view worth millions: looking from the northern block of Dawson's Heights.

In 1964, at just 28 years old, architect Kate Macintosh was given the job of designing Dawson's Heights in south London.

Working for the Southwark local authority, Kate was given a job which today is almost unthinkable - the freedom to design new London housing on a large plot of vacant land. With strongly socialist parents and a clear drive to help generate social justice through architecture, Kate was given the opportunity to deliver a scheme which would stand the test of time.

Clearly, it has.

Decades later Dawson's heights is now considered 'one of the most remarkable housing developments of the country'.

As I walked through Dawson's Heights' many street-like corridors, and entered into its beautiful modernist flats, it was clear to me that this building was designed with a different agenda compared to developments today.

It was built with a genuine ambition to create a community, and a more just society. Every decision that Kate made had logic to it: blocks were oriented to increase sunlight to flats, room arrangements were such that every flat had a balcony, levels were split to improve acoustics, and the building's form and massing ensured an abundance of green space and views across the city from its public corridors.

Whether through a change in political-will or a shift in the behaviour of our markets, architecture may re-emerge as a discipline which seeks to fix societal problems.

Until then, at least we have reminders from a time when it did.

If you're interested in exploring London's most incredible buildings, be sure to check out Open House 2017.