Sydney’s transportation network is in crisis. Decades of dependence on the car have left the roads congested, the air polluted and residents - well – fat. Furthermore, with the city’s cheaper housing stretching out into its vast western suburbs, expensive and lengthy commutes have perpetuated the growing divide between the rich and poor. But we all know that cars in cities really are a thing of the past. Over the past couple of decades there has been mounting evidence that building more roads does not alleviate congestion and traffic within urban areas.

On top of research, dependence on the personal automobile is something that millenials no longer value or desire. Unlike American films of the 1970s, young people don’t want a car for their 18th birthday. In fact, an American study has found that driving by young people decreased by 23 per cent between 2001 and 2009. Today, people want to live in walkable neighbourhoods, close to places of work, education and friends. And surely, no one wants to be the designated driver.

Driving a car simply doesn’t offer a person in the city the freedom that your own two feet or a bicycle does.

For a long time, I dreamed that Sydney would embrace a cycling culture modelled on the success of Copenhagen. Copenhagen’s street design allows children to bike around cruise safely and freely, and encourages spontaneous social interaction during the daily commute.

Unfortunately, I began to give up on that dream sometime in my early 20s. I’m not sure if it was the time I was doored by a taxi on Oxford Street, the time I was thrown to the ground by a cop for riding on the pavement, or the time a guy in an SUV tried to ‘intimidate’ me by actually drive right into me. Or perhaps, it was one of the many other times that I feared for my life because a car driver didn’t see me.

After years of abuse on the roads, it’s become hard to imagine that things will ever change.

While the problems faced by bike riders may seem commonplace in many cities across the world, other cities are changing very quickly. And Sydney is not keeping up.

In many cities, we are seeing an urban transition. New York, LA, London, Paris and Mexico City, to name just a few, are all investing heavily into bicycle infrastructure, lowering speed limits and planning new transit networks. Even China is realising the transformational effects biking and cycling infrastructure can play. Hangzhou recently opened the world’s largest bike share network with over 60,000 bikes and almost 2,500 docking stations.

This is more than just a trend. By incorporating best practices in cycling infrastructure, cities across the world are seeing improved public health, a decrease in congestion and improvement to retail in high streets. Forward-thinking local governments realise this and start building segregated bike lanes and other cycling infrastructure – not more roads.

So, what's stopping Sydney?

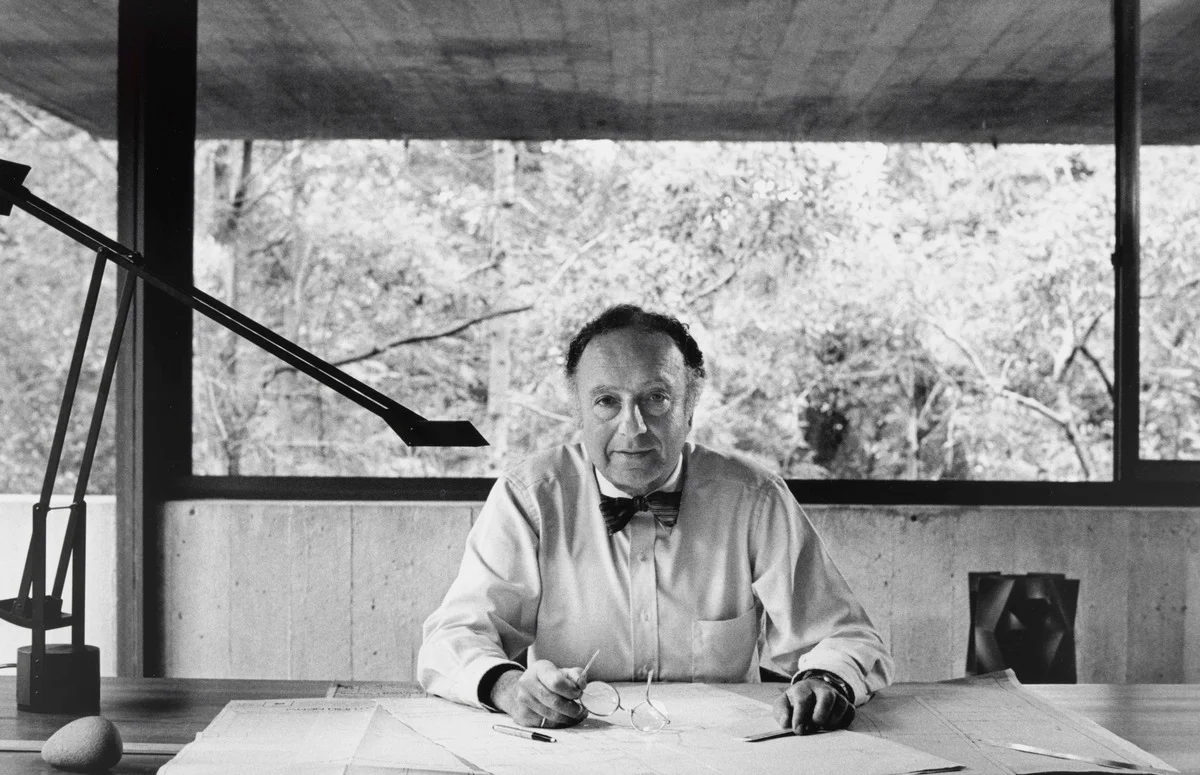

In most conversation about bikes in Australian cities, you hear all sorts of strange arguments. ‘It’s too hot’, ‘too hilly’, ‘we aren’t dense like European cities’. In his book, Cycling Space, Tasmanian-based architect and academic Steven Fleming has shown us how ridiculous these arguments really are. Cities with some of the most extreme temperatures or have built environments characterised by massive amounts of sprawl have far higher levels of cycling than Australian cities.

The major problem in Sydney is poor communication. More specifically, the problem with Sydney is the Daily Telegraph.

New York has recently invested in miles of bikes paths and a hugely successful bike share system. Yes, there has been a lot of debate about these changes in the media. But the debate has been relatively balanced and healthy in the media.

Unlike New York, Sydney doesn’t seem to enjoy a very healthy dialogue in mainstream media. Particularly when it comes to a conversation about bikes. It’s not a debate when the media is dominated by Rupert Murdoch.

For months on end, we’ve seen article after article in what is a blatant attack on pro-bike politicians, policies and journalists from the Daily Telegraph. And the problem with any democratic planning system is that poor communication easily leads to poor decision-making.

But it gets much more personal that that. The way in which cycling ‘accidents’ are portrayed in the paper is downright disgusting. Roads were built for bikes and people, not cars. Yet cars take the lives of dozens of riders every year. How dare the telegraph misrepresent cycling deaths by blaming improper safety equipment. Cyclists are vulnerable road users and cars are to blame.

Sydneysiders know what’s good for our city. We know that more roads are a not the solution. So why do we put up with it? The generation before us didn’t.

Sydney’s Green Bans of the 1960s and 70s were a struggle that helped to give people in Sydney the freedoms they have today. Glebe, Redfern, The Rocks and Centennial Park, would not be the beautiful places they are today if it weren’t for Jack Mundey and the BLF.

Throughout the 1970s thousands of people joined a movement to ensure that the physical nature of our city was protected, preserved and enhanced, not destroyed by oversized development and inner city motorways.

If we want to see a better Sydney, it’s time we collectively stood up to bad press and poor planning decision. Write news articles, share experiences, tell planners that you wish to ride your bike safely and freely. It’s time to take the development of our city out of the hands of Murdoch and into our own.

No, Sydney is not a European city. But now is the time to make it just that little bit more like one.

Feature image courtesy Amsterdamized.