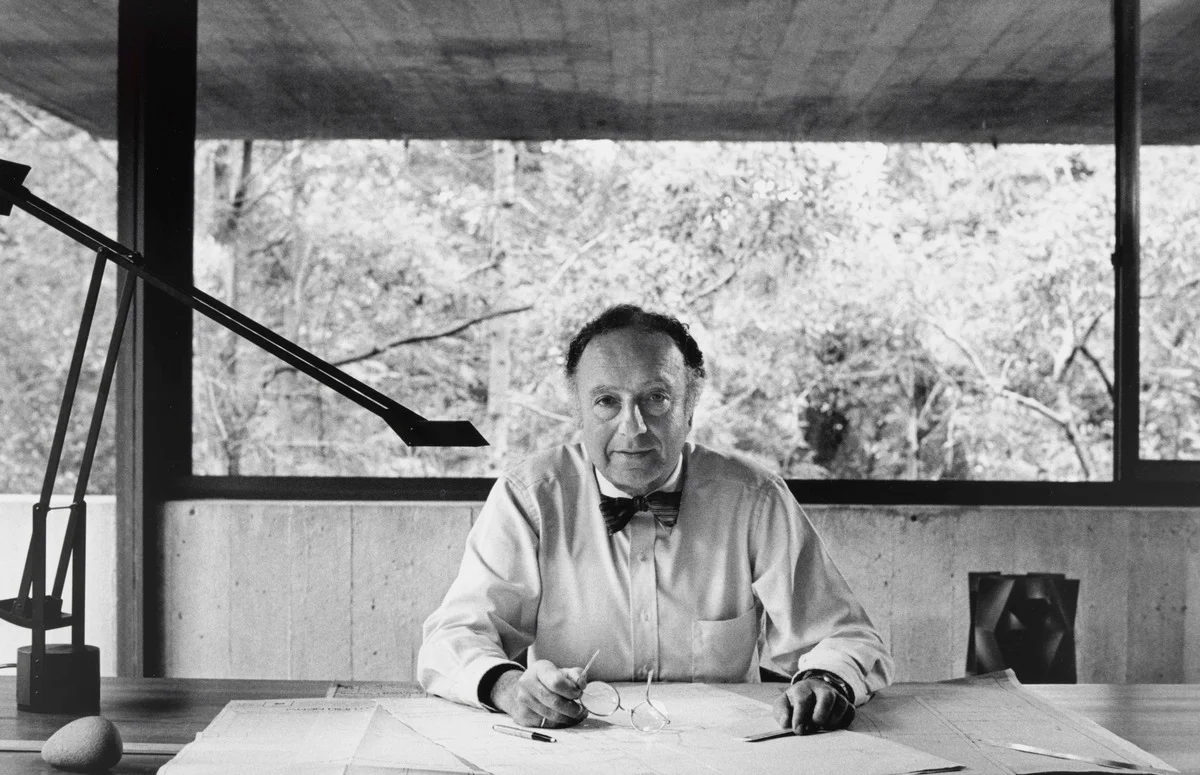

Casino tycoon James Packer, is bidding to build a resort-style casino on the Sydney's most central and beautiful foreshores - Barangaroo.

Every city has had its planning blunders. In fact, a number of monstrosities are probably being constructed near you right now. I’m sure you can name a few. Too often mistakes are made today because past errors have been too easily forgotten.

Throughout the 60′s, the Sydney construction industry was booming; skyscrapers were being erected across the central district, new motorways were extending into the vast suburbs and ex-industrial foreshore sites were quickly being developed into large housing estates as industry moved further inland. “Brave new world” masterplanning techniques embedded the development industry and the city saw the loss of some of its oldest buildings and most vital green spaces.

The Green Ban movement of the 70′s changed all of this. Between 1971 and 1974 around 40 construction bans were imposed by the Builders Labourers Federation to prevent the destruction of buildings or green areas. The most controversial was the ban to halt the redevelopment of The Rocks. After years of strikes and bloody confrontations, the plan to redevelop Sydney’s oldest suburb was altered to ensure strict preservation of historic buildings. Today,The Rocks is one of the city’s largest tourist destinations.

So, what did Sydney learn from the Green Ban movement? According to the new plans to redevelop Barangaroo, not a lot. While the bans did reform planning policy and change the development culture of the entire nation, it seems that in 2013, all has been forgotten.

Casino tycoon James Packer, son of the famous Kerry Packer, is bidding to build a resort-style casino (alongside multiple office buildings) on the city’s most central and beautiful foreshores – Barangaroo.

Interestingly, Barangaroo sits just down the street from The Rocks. So, with this in mind one would hope Packer has carefully considered the area’s history but it doesn’t look like it. All Packer seems to care about his how his “iconic project” can compete with Melbourne and China. With so much support for his development, it seems that the rest of the city has forgotten as well. If we’ve learned anything from Sydney’s past, it’s that the preservation of itsnatural features, particularly the harbour and foreshores, are what has made it such a globally attractive city.

Cities don’t succeed by copying others. Rather, they become far more unique and exciting by learning from their mistakes and enhancing their best features. I don’t know about you, but I’d say another tacky casino doesn’t seem to fit that mould.

Click here to check out this article on the Urban Times.

Feature image courtesy aussiegall/Flickr.