Last week I was making a trip from Sydney to London so I decided to stop off in the south of Sri Lanka for a few days. Colombo was incredible: people, street food, construction, colour and chaos. I also jumped on a train south to check out Galle and Unawatuna, where I had a great time surfing.

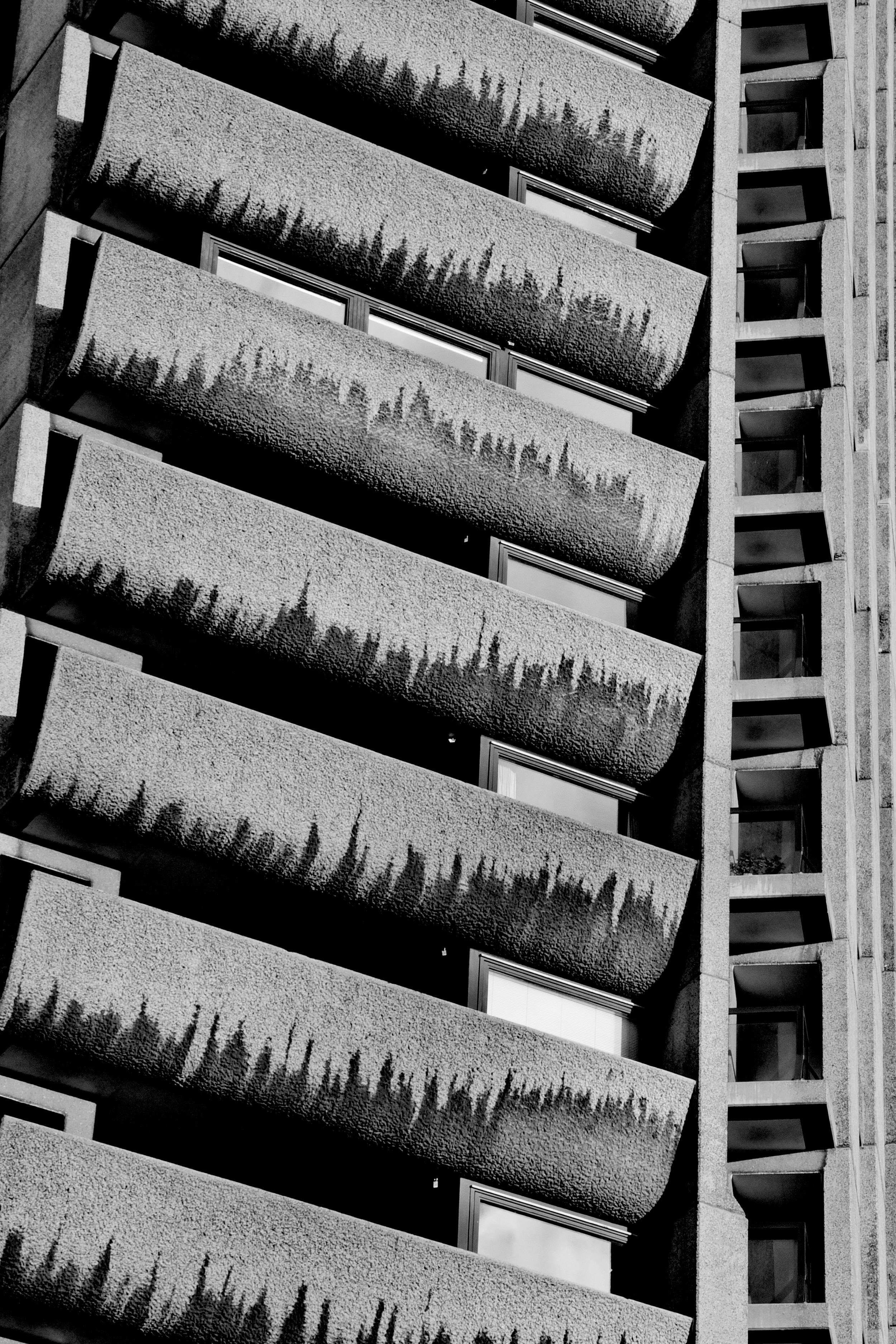

The thing that struck me most about Colombo was the tall building construction boom. It seemed that everywhere I looked were towers being built. The entire southern edge of the city has been earmarked for development and will soon be the "Colombo International Financial Centre'. China is investing US$1 Billion into the project, which will include at least 3 60 storey towers.

Across the city dozens of other tall buildings are now reaching into the sky. It'll be super interesting to see how Colombo evolves over the next decade. Street photos and a short film below.