I wasn't really sure what to expect in terms of bike culture before arriving in Stockholm last week... From what I knew, Malmo in the south is one of the most bicycle-friendly...

Read MoreCongratulations 'Long Live Southbank' /

This week we've heard the incredible news of the win for the Long Live Southbank campaign....

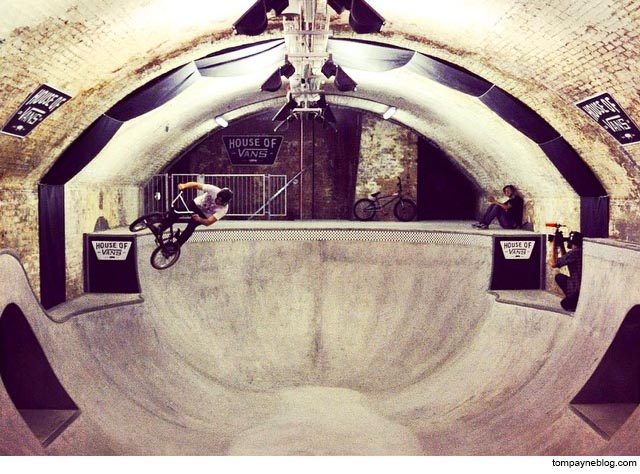

Read MoreI went to London's new Vans Skatepark tonight /

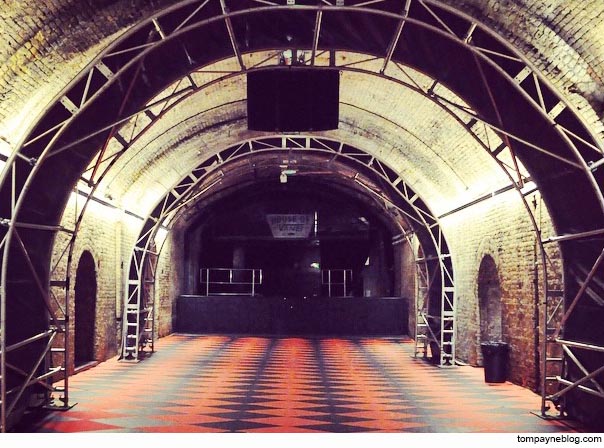

The Old Vic Tunnels underneath Waterloo Railway Station was - just a few years ago - nothing more than a few damp and derelict railway arches. In 2009 the space opened its doors as an arts and performance space and hosted dozens of amazing musicians, including the amazing Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros and saw the UK premiere of Banksy's Exit Through the Gift Shop.

After more than a year in disuse once again, the space reopened just a few weeks ago as House of Vans. Luckily enough, I was able to check out the new venue a few days after it opened. It's pretty amazing.

Nestled away in the Leake Street corner of the Station, the space comes complete with a street course, bowl section, a couple of bars, art space and music venue.

Once again, London has proved that innovative and creative thought to architecture and design can over come even the tightest physical limitations. When compared to the Vans parks spread across the United States, the London setup looks a little small. But through incredible layout technique, the creators of this venue have somehow managed to create what is a probably a far more interesting and active space than any large warehouse could offer. The coolest part is that it sits just a few metres underneath a a major railway line in the midst of one of the most amazing city centres in the world.

Perfect for an afternoon skate, Friday night party...or both. Check it out.

Feature image courtesy Domus. Images above by Tom Oliver Payne.

Are England's seaside arcades a thing of the past? /

Southsea. Photo courtesy Flickr/BMiz/CreativeCommons

Neon lights, sticky carpets and non-stop beeping sounds are engrained into the character and charm of English seaside towns. For decades, locals and tourists alike have flocked to the arcade to spend their spare change on games that would now be no match for even the most simple of iphone apps. Are amusement arcades a timeless piece of English culture, or are they nothing nothing more than outdated and tacky relics of the past?

Amusement arcades boomed throughout the 70s and early 80s when private computer games were non-existent and Space Invaders, Pac-Man and Frogger seemed to be ever-growing in popularity. As private computers and consoles launched onto the scene in the 90s, it's no wonder traditional arcades experienced a decline. Technology wasn't the only change to impact the arcade, anti-smoking and gambling laws were large scale societal changes which altered the way we utilise and perceive indoor entertainment space.

But despite all of this, the arcade has survived.

As I rode my bike through Norfolk at the weekend, the local towns were filled with arcades packed to brim of families holding ice-creams, reaching into their pockets for another round of Nascar. If arcades aren't the innovative places of entertainment they used to be, how do they exist?

Going to the seaside is something of a spectacle in the UK. But in one of the world's drizzliest countries, it's not always possible to sit on the beach all day. The arcade's iconic architecture, wide doorways and expansive internal layouts, depict the arcade's ability to offer leisure in what seems and feels to be a very public space.

While entertainment may come at an expense, much like a good cafe or pub, arcades offer an internal public setting to what is often a cold and drizzly outdoor world.

Sydney's Broadway is getting a facelift /

Courtesy Central Park Sydney.

A bunch of interesting developments have come alive in Sydney's broadway region over the past few years.

The scheme at Central Park has been well-received on both the local and international scale. The 235,000 sq m mixed use scheme has given the city a fascinating new addition to the skyline, has added some much needed public space and has set the bar with regard to environmental building standards. Designed by Jean Nouvel, One Central Park was ranked by Emporis as one of the world's best skyscrapers and ranked as Australia and Asia's best tall building by the Council for Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.

The $1 billion UTS masterplan adjacent to Central Park promises a range of access routes and public space and of course, a host of new buildings throughout Ultimo - one of which has been designed by Frank Gehry. The Dr Chau Chak Wing Building, named after the Chinese-Australian business man and philanthropist, will accommodate 1,300 students and 400 academic staff in a unique tree house structure.

Both of these buildings provide an architectural quality that will be easily distinguishable from a city that still primarily comprises 1960s modernist towers. They also indicate something that's occurring at a much wider scale. With a new wave of tall building construction, Sydney is forming a distinct and interesting urban aesthetic. Hardly the destructive construction boom that the city experienced during the Green Ban years, these developments appear to be a respectful enhancement of the existing urban realm.

The Central Park and UTS schemes epitomise Australia in its modern context. As new environmental standards, strengthening connections with Asia and a desire for high density living increasingly influence the built environment, new buildings like these help to raise the standard in planning and architecture and positively represent a city to a global audience.

Why Copenhagen's trajectory is not 'negligible' /

Having just returned from my third trip to Copenhagen, I'm super impressed with the city. Not only is there an abundance of beautiful people, great coffee and delicious rye bread, but the city really does seem to be paving the way in urban sustainability.

On the flight home I read an interesting in an Easyjet magazine As Green as it Gets which questions some of Denmark's environmental advancements. In summary, author Michael Booth explains that while the city is incredibly green on paper, this is only 'negligible' due to a relatively small population size and the country's utilisation of huge amounts of coal. Booth also points out that while the intention is there to become sustainable, there are ongoing negative impacts and serious shortfalls, including 'greenwashing' and high energy costs.

While the article makes some interesting factual points, it fails to see the bigger picture. Yes, there are shortfalls in Copenhagen's (and Denmark's) progression to urban sustainability and a green economy, and yes there are ingoing negative implications of achieving positive environmental results. But none of this is 'negligible'.

When looking at Copenhagen's policy and planning decisions while taking into account the idea of path dependence, it is possible to appreciate a much broader and more positive picture.

Every positive action that the city of Copenhagen takes today has implications both nationally and internationally. While some reductions in C02 may seem negligible compared with ongoing coal use, these small advancements are all part of a much wider picture.

Every small improvement is setting a higher standard for the entire world. It's leading us on a more sustainable trajectory. Just as companies copy good ideas, cities copy cities. Look at the Copenhagen's ability to plan for bicycles for example - all of a sudden, the world wants to 'Copenhagenize'.

So, while Booth makes some interesting points, it's important to remember that often it's easier to criticise a set of processes than to see the bigger picture in a historical context.

Copenhagen's advancements in environmental technologies, architecture and planning are incredibly impressive. Of course there are shortfalls, but the evolution along current trajectories will only make the city more liveable and sustainable in the long-term. And it's through the evolution of these more sustainable trajectories that we're likely to find alternative solutions to some of the world's greatest problems, including the utilisation of coal energy.

Rather than nitpicking, perhaps cities across the world should be watching Copenhagen much more closely.

Photos by Tom Oliver Payne

I wandered around Singapore. Here are my thoughts on the city. /

At my past job at a sustainability charity in London some of my friends who had lived in Singapore explained that it was highly ambitious environmentally, giving numerous examples of green business parks and ambitious building standards. But chatting to a cab driver over the weekend in the city, he had a slightly different perspective.

Explaining the ongoing peripheral urban development and housing crisis, it seemed that the island/nation/city continues to grow rapidly to its own detriment. "What's that word?" he said, "Urban jungle! This nation is turning into one big urban jungle!".

While land intensification has been an ongoing policy for development in the city for many decades, it does continue to slowly sprawl into the periphery to accommodate the rapidly growing population. Comprising only 270 sq km in total, land development issues in Singapore can be seen to epitomise land use issues across the globe (just on the small scale). We want urban 'growth' but how do we stop expanding?

I'd definitely need to spend some more time in the city to have a better perspective on sustainable development in Singapore. It's such an incredibly interesting city that seems to be developing very sensibly, but could it be doing even better? And what lessons can other cities learn from Singapore as an example?

Apart from all of the big picture strategy stuff, I made the following brief observations from my quick day of walking about the city: high density, manicured gardens, not pedestrian friendly, ambitious, colourful, beautiful, amazing food and smells and of course, hot and humid! If the city had a little less cars, a few more bikes and made a bit more effort in place making and public space creation, it'd make all the difference.

I'd love to know other people's thoughts!

All photos Tom Oliver Payne.

A talk by Lord Richard Rogers: Architecture and the Compact City /

This is an awesome talk, particularly interesting for someone like myself who lives across Sydney and London. So much to take from this. I think most importantly are the Rogers' final principles for what he calls an 'urban renaissance'...

Read MoreWhat could cities learn from La Défense, Paris? /

I've written once or twice before on the glass and steel enclave that is Canary Wharf, in London's east. La Défense could be regarded as the Parisian equivalent. While their histories differ significantly, their purpose is somewhat similar: they offer space to alleviate the cities from the pressure from intense commercial floorspace demand.

Apart from Montparnasse (and of course, the Eiffel Tower), Paris has - throughout history - enforced strict restrictions on building heights. During the 60s and 70s, as the economy became increasingly focused on services sectors, demand for office space boomed. As a result, La Défense attracted large-scale property development because it was able to offer the space for vertical growth.

With property demand remaining strong across Paris, solutions to the problems facing planners today are not simple. The city juggles the needs of economic and population growth with transport congestion and historic conservation.

La Défense is no quick-fix. In fact, channeling thousands of workers into this major office hub places immense pressure on city systems. However, unlike London which has recently allowed for height increases across the core, Paris refuses to relax downtown height restrictions. As London's large commercial schemes now spread from Canary Wharf right across the West End, Paris remains focused on concentrating its major office developments in La Défense. The government is supporting this with an ambitious 9 year investment plan.

Which model works best? Will Canary Wharf suffer from the inner city developments which act to siphon demand? Will La Défense fail to produce what international investors expect in a world class city?

Heading over to the La Défense precinct last week, I was impressed with the unique architecture that lines the wide pedestrian plazas. The symmetrical landscape design and interesting building shapes offer an aesthetic touch that many city's don't. But would I want to work there? Probably not.

While it is beautiful, La Défense lacks the small-grain character that is vital to urban vibrancy - a characteristic that makes central Paris so special in the first place.

Rather than a blank criticism, this is just one simple observation of a district that I believe offers immense opportunity to solve a number of urban growth problems. If Paris can get it right through Project La Defense 2015, the area will act as a wonderful example of how to balance the needs of market-driven growth with historic preservation. As London's skyline looks bound to further fragment, perhaps there are lessons to be shared in both directions.

All photos by Tom Oliver Payne.

Music and architecture... Vito Acconci, the optimist! /

"Both music and architecture make a surrounding. They make an ambience. But also, both music and architecture allow you to do something else. Something else while listening to music..."

Read MoreWithout Urban Strategy, is Australia Planning to Fail? /

National governments across the globe are showing a growing appreciation for the economic importance of cities. In taking an increasingly strategic approach to the development and management of powerful economic and cultural urban nodes, they’re attempting to diversify economies and invest money where it matters most. In the wake of the recession, this policy shift has been particularly strong in the UK.

Australia on the other hand, seems to be moving in the opposite direction. With the end of the resources boom in sight, perhaps it’s time ‘the lucky country’ took a long, hard look at its urban agenda. For hundreds of years, we’ve been obsessed with the nation-state paradigm. But the idea of inter-national coordination has largely failed. The United Nations has no teeth, every climate talk since Rio (1992) has failed to bring practical solutions, and the global recession has presented us with panicking national governments with little control over globalised economic systems.

With over half of the world’s population now living in urban areas, we’re seeing the emergence of a network that is more about action than stubborn nationalism. Operating across international borders, our global network of cities forms the economic and environmental collaboration that national governments cannot.

As Benjamin Barber has put it, national governments are based on “ideology”, while cities are all about “getting things done”. Cities are bound together by trade and economics, innovation and entrepreneurship, common attributes and common values. Cities are where things happen; national governments are where politicians talk.

The growing realisation of the importance of cities has sparked policy shifts worldwide: Korea is scaling-up regional city growth to diversify economic activity, Poland has recently developed a national urban strategy to become economically competitive with greater Europe, and Brazil has created a City Statute to give municipalities increased power and finance.

The UK has seen the development of a Cities Policy Unit and a host of new strategies that attempt to create a fundamental movement away from federal power to that of mayors and cities. The newly appointed Minister for Cities has called for a new era to create city systems and systems of cities. The former is concerned with equipping local leaders to strengthen productivity, liveability and sustainability outcomes, and the latter is about actively supporting urban networks as a whole, including connectivity and city specialisation. This includes investing into infrastructure such as broadband, high-speed rail and airports. The Technology Strategy Board has already made substantial investments into the Future Cities Demonstrator and Future Cities Catapult, which aim to enhance urban innovation.

With growing importance on the city scale, urban political leadership is now a hot topic. Charismatic mayors like Boris Johnson and George Ferguson are winning support by implementing real solutions to environmental and economic issues. Less focused on ideology and more focused on answers, its no wonder Johnson has been titled the most popular politician in Britain over his central government counterparts.

Tucked down on the other side of the world however, we’re seeing powers taken from Australian cities and mayors, rather than given to them. After almost a decade of developing a vibrant nighttime economy, Sydney Mayor Clover Moore’s work has been badly bruised by conservative state premier’s controversial new drinking laws. O’Farrell’s arbitrarily located restrictions are not supported by any research to indicate that they will reduce violence. Instead, they look to create late night transit chaos and hamper Sydney’s buzzing nightlife economy.

Rather than developing a strategy based on citywide coordination, it seems the new legislation was an opportunity for the state premier to simply flex his political might. While Mayor Clover Moore is about “getting things done”, O’Farrell’s policies are based on political gain.

Issues such as these are all too common in Australia. As underfunded local councils struggle to coordinate important planning processes with the powerful state governments above, planning and economic development remains an under-resourced, ad hoc process. Australia is in serious need of city systems and systems of cities strategies.

Just two years ago there was progress in making this happen. Australia’s previous government created the Major Cities Unitwhich outlined key long-term priorities for urban productivity and sustainability. Highly regarded by academia, as well as infrastructure, planning and property councils, the Unit showed promise for strategic city alignment, including investment into high-speed rail.

Today, all investment into the Unit has been withdrawn and momentum towards a national urban strategy has come to a halt. Not only does Prime Minister Tony Abbott have blatant disregard for the natural environment but he also struggles to see the importance of investing into research and long-term strategy, even when concerned with economic growth.

Australia remains plagued by a three-tiered governance structure that stifles coordination: citywide governance is fragmented (dozens of local councils with no metropolitan authority), local to state government relationships are a political battle, and federal intra-city investment is non-existent.

Countries affected by recession have worked to develop national policies to diversify industry and build economic resilience. In the meantime, Australia has stood back with its eyes closed. With the resource boom beginning to slow, perhaps now’s the time for Australia to rethink how its cities can develop and integrate into the growing global urban network.

This article was originally written for This Big City and is also available in Spanish.

Feature image courtesy This Big City.

Sydney's Millers Point: the wider issue /

Quickly becoming an enclave for the rich, it's obvious that the city's lack of supply is perpetuating the affordability crisis.

Read MoreIs there an urban creative crisis? /

Cities are not merely creative but capable of generating and nurturing hope, innovation and sense of possibility...

Read MoreSydney's bi-directional bike paths: the wrong direction /

Sydney has demonstrated increased enthusiasm for bikes over the last few years. As someone born and raised in the city, this is something that I’m super proud of.

Read MoreSeven billion people, over half in cities /

Cities are not just buildings and roads sitting the surface of this earth, but they're living, moving, organic and real; they must change and evolve just as human beings do.

Read MoreI am the problem: the gentrification of Redfern, Sydney /

At some point or another, each and everyone one of us likely contribute to this problem. At some point, each of us will also be subject to the negative impacts that result.

Read MoreHow we can design for human desire /

Have you ever noticed a dirt track through a public park or a group of people who meander across a street in seeming defiance of authority?

Well, that's because we, as humans, utilise something called 'desire lines'. Coined by French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, desire lines describe the human tendency of carving a path between two points (usually because the constructed path takes a circuitous route).

Across the globe urban authorities tend to try to control people's walking desires by erecting fences and walls. This illustrates nothing but a disrespect for human desire.

Instead, planners and designers should be acting to adjust urban infrastructure to appreciate the way in which humans utilise urban space.

The image above shows a terrific example from Gladesville in Sydney. Travelling from the city's north into the Inner West, one must traverse a number of waterways. For private cars, this journey is relatively direct and well-signed. For pedestrians and cyclists on the other hand, the journey is indirect and rather complex, leaving people to navigate multiple underpasses and complicated road-crossings. Not what you want on a hot Sydney summer day. As a result, pedestrians and cyclists have forged their own path which allows them to avoid a good 300m underpass walk. Instead of observing and redesigning the space to accommodate for the desires of people, the roads authority has continually tried to stop the movement of people by erecting fences at multiple sections along the path.

Is Sydney a city for people or a city for vehicles? It seems that the Roads and Maritime Services would prefer it to a place for cars (I guess it's all in the name, right?).

As cities move from being overly engineered and private vehicle-dominated, observing desire lines will act as an incredible tool in urban design, place making and urban management.

In the words of Mikael Colville-Andersen, "Instead of erecting fences to restrict them in the behaviour, they [Copenhagen Council] actually make it accessible for them and make it easy for them. Because people - at the end of the day - decide on where they want to go... This is the way forward in designing our cities for people". Check out his great little film below:

Episode 09 - Desire Lines - Top 10 Design Elements in Copenhagen's Bicycle Culture from Copenhagenize on Vimeo.

Feature image courtesy Adventures in Photography.

Meet Gary and Prince of Shoreditch, London /

This is Gary and his dog, Prince. Gary is one of hundreds of people who will sleep on the streets of London each night this winter. If he makes enough money in a day, he may sleep in the local Shoreditch shelter.

Read MorePolicy mobilities, planning cultures and Cycle Superhighways /

I recently had the opportunity to complete a dissertation on a topic of my choice. As expected, I decided to research bikes in the city...

Beginning the dissertation I envisioned undertaking a fairly straightforward analysis of how London has attempted to copy Copenhagen’s Cycle Superhighways (CSH). As with most research, it wasn’t long before I realised that the delivery of each of these policies wasn’t as straightforward as it first seemed.

While London and Copenhagen’s motivations for implementing CSH remained generally the same, their designs could hardly be more distinct. London’s blue splats of paint are hardly the safe and coherent, segregated cycle paths that stretch into and out of Copenhagen’s centre.

In reality, London has made no effort to actually ‘copy’ Copenhagen’s CSH network: it has merely copied the name.

While cycling around Copenhagen in the glorious summer months conducting an urban design analysis and interviews with planning professionals, I was faced with the complex question: how can London improve its cycling culture to become more like that of Copenhagen?

The answer is essentially quite simple: build it and they will come. But why has this been so difficult in London? Why does every cycle scheme ignore the need to build infrastructure that separates bikes and cars?

It wasn’t long before I was exploring the histories of both cities, making links between past events and contemporary transport planning culture.

On the one hand, Copenhagen has decades of experience in implementing segregated bike lanes (although it wasn’t always this way). On the other hand, London has a long history of implementing lousy, ad-hoc cycling schemes, which in a sense, continually try to please everybody, without actually pleasing anybody. This continues because of the status-quo mentality that runs deep within bodies like Transport for London.

How can London get out of this rut? With such a democratic approach to planning, how can it begin to finally close the ‘cycling credibility gap’ (relationship between acceptance of cycling culture and the level of infrastructure) - as I've termed it – without already having critical mass?

As a final recommendation, I’ve argued that London (ie. Boris) must finally begin to deliver sections of high quality cycling infrastructure. By communicating the benefits of fully segregated cycle paths, he can finally gain the momentum to persuade the lobby groups, institutions and various road users that this is exactly the long-term infrastructure London needs to become the cycling city it envisions itself to become.

Check out the full dissertation here: Policy mobilities, planning cultures and Cycle Superhighways (note: names of interviewees have been removed for privacy).

How micro-financing can help create sustainable cities /

Cities are experiencing rapid growth across the Global South. With this growth however, also comes economic disparity and environmental degradation. Can micro-finance offer a solution to these growing concerns?

One hundred years ago, just 2 out of 10 people lived in urban areas. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 5 out of 10. The number of residents in cities is now growing by about 60 million per year and is expected to increase from 3.4 billion in 2009 to 6.4 billion in 2050. Almost all of the urban population growth in the next 30 years will occur in cities of developing countries – much of which will be across Asia.

It’s estimated that Bangkok for example, will expand another 200 kilometres from its current centre over the next decade.

Rural to urban migration across Asia is occurring on a scale never seen before. Another 1.1 billion people will live in the continent’s cities over the next 20 years. It’s anticipated that in many places, entire cities will merge together to form urban corridors, or what some refer to as ‘megalopolis’ regions. It’s estimated that Bangkok for example, will expand another 200 kilometres from its current centre over the next decade.

With mass urbanisation has also come significant concern with regard to economics disparity and environmental sustainability.

From one perspective, rural to urban migration is thought to be helping to alleviate poverty by pushing more people into the middle class. Additionally, increased urban population density is seen to be ‘green’ because it lowers dependency on private vehicle use and increases resource efficiency. From another perspective however, mass urbanisation also causes a variety of problems across a range of geographic scales: socio-economic inequality, slums, sprawl, deforestation, air pollution, excessive waste and poor water management, to name a few. There is no ‘silver bullet’ for these problems.

While significant research is being conducted into how governments can best manage large-scale rural-urban migration, many troubles resulting from mass urbanisation are largely out of government control. One of which is access to finance. In order to gain a foothold in the city, new migrants require money to look for housing, initiate a business or find a job. With low levels of excess income and no permanent address, this is not as easy as walking down to the local bank branch and asking for a loan.

The inability to obtain capital can place new residents into financial traps. Burdened with huge overheads, people are forced to borrow and operate through the informal sector. While informality is not necessarily a bad thing (providing jobs, housing and networks where they may not normally exist), its unregulated nature can also lead to unethical and unsustainable business practices. In the longer term these practices can exacerbate poverty and environmental degradation.

Lendwithcare.org was launched in late 2010 as a branch of Care International, in association with The Cooperative. Allowing people to make small business loans to entrepreneurs in developing countries, and it gives people the opportunity to climb out of poverty.

Already active in Cambodia, Togo, Benin, The Philippines, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Ecuador, the programme has experienced particularly high growth in Asia where we’re seeing large scale rural to urban migration. To work with this growth Lendwithcare.org has recently also become operational in Pakistan.

The programme works with a number of partner microfinance institutions (MFIs) in the countries in which it operates. If the MFI is happy with an entrepreneur’s idea or business plan, they approve the proposal and provide the initial loan requested. Once the entrepreneur’s loan is fully funded, the money is transferred to the MFI to replace the initial loan already paid out to the entrepreneur.

The great thing about all of this is that microfinance is in and of itself “green”. Put simply, it promotes businesses that can be sustained indefinitely. When those living in poverty are given the opportunity to earn a living in a legitimate and sustainable manner, they have no need to become involved in unethical or unsustainable practices. Additionally, most organisations involved in microfinance such as Lendwithcare.org, hold sustainability as a precondition for awarding loans. Others may encourage greener businesses by offering lower interest rates to borrowers with sustainability-oriented plans.

Already programmes like Lendwithcare.org are having incredible impacts on the environment in places where it’s needed the most.

Here’s an example. Approximately 84% of people living in The Philippines depend on motorised tricycles for transport – 70% of which have polluting two-stroke engines. As you can imagine this is having a devastating impact on the environment as well as on the health of urban residents. While the local council of Mandaluyong City in Manila has recently enacted legislation requiring all tricycles to switch over to cleaner liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), this requires a significant (and often unaffordable expense) for tricycle taxi drivers.

This is where Lendwithcare.org comes in. Committing to local partner Seedfinance is now raising $25,000 in order to provide smaller loans of $500 to 50 motorized tricycle taxi drivers in Mandaluyong City so that they can pay for their vehicles to be switched over to LPG without crippling their livelihoods.

This highly ambitious project has the ability to alleviate poverty at the local scale, while ensuring that important urban sustainability targets can still be met across the region. By assisting ethical entrepreneurship, microfinance ensures that economic and environmental sustainability go hand in hand.

Writing once before on the innovative business models that are helping to create a more just and sustainable world, I’m quickly beginning to realise that the traditional corporate model is diminishing.

As urbanisation rates continue to soar across the globe we’re beginning to appreciate the incredible networks that are unfolding between the public, private and not-for-profit sectors. These networks are producing outcomes that promise to benefit more than just corporate shareholders.

Feature image by Tom Oliver Payne.