Having played music on streets across the world, at 29 years old, busker and musician Kane Muir has experienced a life unique to most. Before he embarks on his next stint in Los Angeles, I caught up with him to talk cities, warehouse-living and the busking lifestyle.

Read MoreWorld

4 insights into the future shape of cities /

Since I was a kid I’ve been fascinated with futurism, and in particular, the future of cities. Naturally, I was super-excited when MINI invited me along to the ‘Future Shapers’ event.

Heading to London’s Roundhouse last Monday, I had a little think back to how the world has changed in just my lifetime. City skylines were smaller, the internet had hardly been invented, and Walkman’s were still high tech, portable technology. How could anyone back then have ever imagined the world we live in today?

As I entered the bright and beautiful auditorium, I grabbed a beer and had a chat with a friend about the innovative technology we were probably about to see. I guessed intelligent, self-driving cars. He guessed new car to mobile app technologies.

But as Mark Adams, Head of Innovation at Vice, took to the stage, we quickly realised that the future that we were about to vision, was not just about creating the newest and best technology, but was also about innovating our ways of thinking.

Here are 3 of my favourite insights into the future of cities from the event.

1. Cities will be collaborative

Speakers with expertise in psychology, property and design took to the platform to speak about the importance of ‘collaborative consumption’ and the need to address global problems by evolving into a society which shares.

It only takes looking around a city to realise that the way we eat, live, and travel is unsustainable. And with the world’s population growing so quickly, it's easy to see that at our current rate, it won’t be long before we all run out of clean air, clean water, or simply, space to live and move.

But by sharing buildings, cars, bikes and services (made possible with apps), we’re quickly evolving into a society which can better reuse, rather than waste. It won’t really matter who owns what, because at the end of the day, by sharing, we all save time and money. It just makes sense, right?

2. Less will be more

Gone are the days of mass consumption, sterile shopping malls, huge cars and unnecessary gadgets. The future of cities will be about minimising everything from the space that we use on streets, to the time that we spend getting to and from work to maximise time with hanging with friends and doing the things we love.

Already in the past decade or two, young people have opted for smaller, shared housing in urban areas to cut down on travel times. In places like Japan, we’re seeing young people completely cut down on possessions altogether.

Our parent’s generation was the era of consumption, but this century’s urban generations are more satisfied with experiences over things. Sharing a car and flat won’t be a problem when your possessions comprise just a couple of digital tablets and maybe a bike and book or two.

3. ‘Mobility’ will replace ‘cars’

Once only a possession for the wealthy classes, the 1950s saw cars become a product for the masses: people were given freedom to move where they wanted – whether in a city, or between cities. They became a symbol of adulthood, freedom and independence.

But it wasn’t long before the car began to dominate. Roads and car parks ripped through city centres as we became unhealthy dependant on the machine with four wheels. But by recognising problems with congestion and pollution, brands like BMW are now part of the solution to quickly improve urban transport, and help the natural environment.

Explaining that car parks now comprise 30% of our cities, futurist Magnus Lindkvist, told us how cities of the future will improve by swinging back the pendulum away from car dominance.

Instead of simply talking about ‘cars’, we will talk about ‘mobility’ – an integrated urban system of bikes, cars and public transport. We will choose our transport options based on efficiency, comfort and style, depending on what we feel like, and when.

The cars we do choose to use will be compact, energy efficient, beautifully designed, and constructed from high quality materials, such as the brass and copper comprising the inside of the MINI Vision Vehicle.

Lasting decades rather than years, and carrying dozens of people across cities each day, cars of the future will be a beautiful and efficient addition to our cityscapes. Just like a good watch, they will be cherished and maintained.

4. Our world will be personalised

Every one of the 7 billion humans on this planet is unique. So why not make objects and environments just as unique as we are?

Last month I met designer Ross Atkin, who is using digital technology to personalise our streets for the blind or less abled. I was super impressed with his work – which is both inspiring and practical. By using technology and data which already exists, Ross’ work can improve the lives of millions.

But as artists Margot Bowman and Marcus Lyall took to the stage on Monday night, I realised that the future of personalisation won’t just stop there. These artists work at the intersection of art and technology, creating bespoke environments which respond to our needs, wants and emotions. Not only can technology help to solve problems, but it can also enhance our day-to-day experiences and pleasure.

As Anders Warming, Head of Design, MINI, showed us how the MINI Vision Vehicle will respond to our emotions through lighting, I started to foresee an urban future which only a few years ago was completely unfathomable.

Objects will no longer just be objects. But just like my smart phone rather than my chunky old Walkman, future belongings will become completely integrated into just about every aspect of my life.

Helping us to move, plan, manage and organise, we create more time to do the all things we love.

Heading along to Monday’s event, I thought I would be checking out some cool technology and design ideas. But I had no idea that the conversation around the future would open my mind to so many interesting insights into the way we might behave, and perceive the world around us in the future.

It made me super excited to see the shape of things to come. I’d love to know your thoughts – what is your ideal future city?

The BMW Group Future Experience, showcasing MINI’s Vision Vehicle is taking place at the Roundhouse in London until Sunday 26th of June. Visit www.mininext100.co.uk or @MINIUK for more information. #MINI #NEXT100

Feature photo: Mark Fischer

Urban photography needs snap judgement /

Taking good urban and architectural photos requires snap judgment to capture spontaneous city moments.

I usually find I get the best shots when I’m least expecting it – the light may looks particularly nice when I’m out to meet friends, or the roads may be emptier than normal on my way to work. But because carrying a big DSLR camera around can be pretty damn awkward, I’ve been waiting for the day that a camera phone is just as good in quality.

After hearing that EE was bringing out the Huawei P9 co-engineered with one of my favourite camera companies, Leica, I was super keen to try it out. Thanks to EE, it wasn’t long before I had one in my hands on one and was heading out for a day on my bike in London.

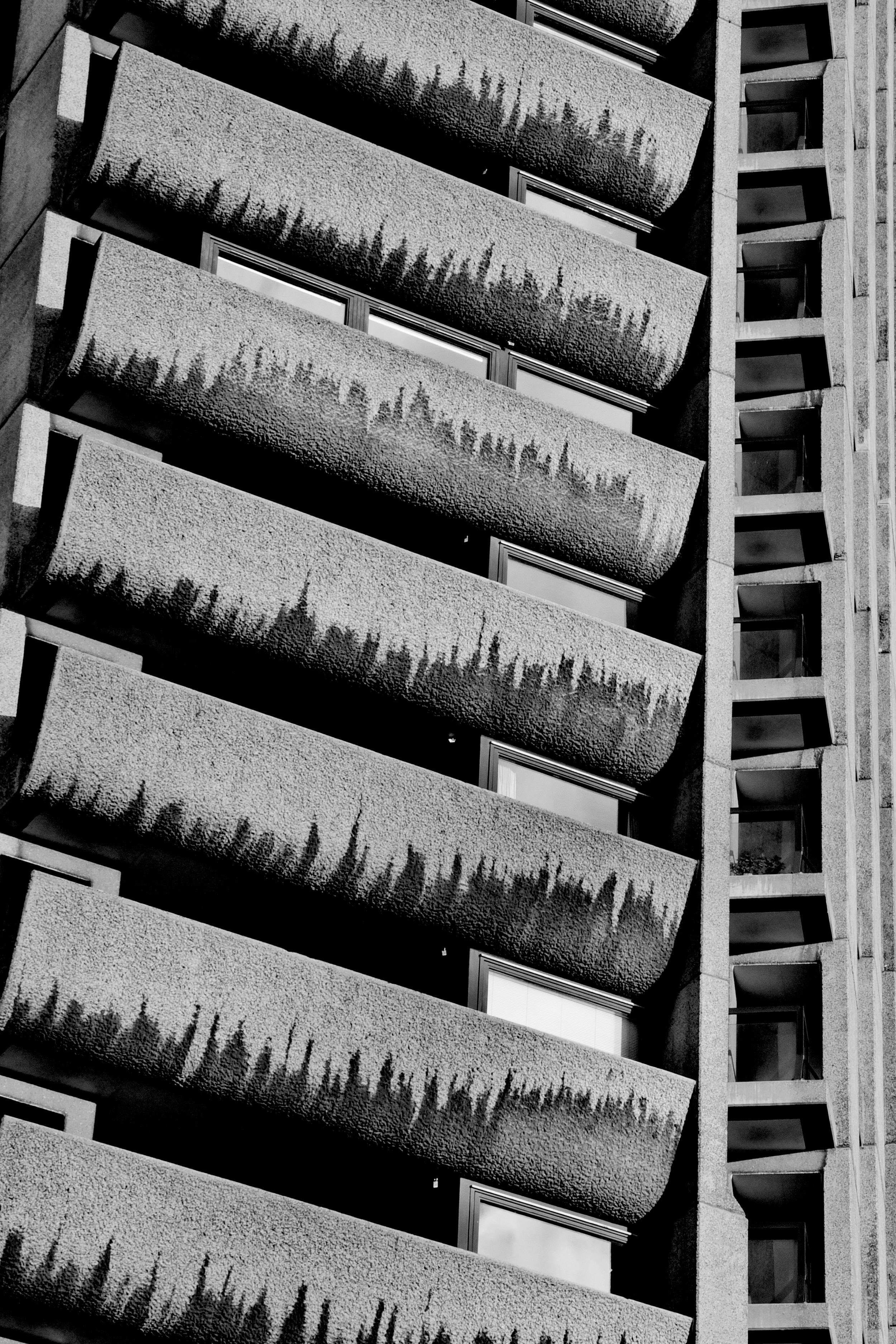

Riding towards Canary Wharf, I checked out some Brutalist architecture in London’s east end. From Balfron Tower to the Isle of Dogs, I meandered my way through dozens of estates, capturing the shapes of the concrete buildings around me.

Lying awkwardly in the grass, trying to get a photo of famous 1970s, Robin Hood Gardens, I was approached by an elderly man who told me that the buildings would soon to be demolished. I suddenly appreciated the ability to capture these buildings at this moment in time, right before the neighbourhood was to vanish… And who knows, the photos might even be worth money some day.

As I crossed into Canary Wharf, I was amazed by the sudden contrast from the 1970s concrete buildings I had just left to glass and steel now towering above me. I was now looking at some of Europe’s tallest skyscrapers - all mirroring the beautiful blue sky and fluffy clouds above. While I would never want to live or work in this financial district, I knew that when the sun was out – like it was today - it was an awesome place to photograph.

As I pointed the Huawei P9 towards the towering office blocks above, I appreciated the camera’s wide lens, which helped me to fit the enormous buildings in frame. This is something I’ve always used on my DSLR, but have never had the benefit of on a camera phone. And just like my camera, the P9 also comes with manual features like shutter speed and ISO, which enabled me to make the most of the heavy shadows over me when converting to black and white.

I soon found myself riding through London’s city centre, photographing the strange triangular shape of the Leadenhall Building, the dome-like roof of The Gherkin and the rugged rawness of the Barbican Estate. After a week of rain, I couldn't have asked for better weather to shoot in.

Towards Tower Bridge, I was confronted by a bottleneck of traffic, and soon realised that the bridge had risen to let a boat pass through. After years of living in this city, I’d never seen this old bridge open its gates.

Just as a cyclist rode ahead of me, the road over the bridge ahead lifted itself vertically. I quickly took out my phone and grabbed a shot of the man on his bike in front of the vertical road. As I looked at the photo I’d just taken, I realized how few people would have had the opportunity to capture such a moment. Standing in the middle of one of the world’s most famous bridges, I snapped a view that few others had seen. A spontaneous moment forever recorded - I was quickly falling in love with having a high quality camera phone.

As much as I love my DSLR, taking the P9 out for the day showed me that the concept of the camera phone has now been reinvented and can almost compete with even the best digital cameras. Unlike DSLRs however, it fits straight in my pocket, ready to capture any moment, at anytime. The marriage of EE’s super fast network and dual lens camera makes the Huawei P9 the perfect smart phone when I’m on the road and want to capture spontaneous moments.

All photos taken on the Huawei P9. In collaboration with EE, the 4G Network that’s 50% faster than O2, Vodafone and Three.

Creating digital cities: Interview with Ross Atkin /

Time is flying, and the world is developing at a rate of knots. Blink and we’re onto the next iteration of iPhone. The world is changing, and quickly. I mean, who knew that it’s been 100 years since the first BMW went into production. To mark its centennial year, the BMW Group and its four brands – MINI, BMW, Rolls Royce and BMW Motorrad, are exploring groundbreaking technology that will affect how we live over the next 100 years.

MINI particularly has always been recognised for its personalisation in design so it’s fitting that as part of the centenary year it has created the ‘Future Shapers’ project. Bringing together cutting edge designers Marcus Lyall, an audio-visual director, Margot Bowman, a multi-media artist, and Julia Koerner a fashion designer, to explore the future of personalisation in design, technology, fashion, and mobility.

MINI’s project inspired me to find other pioneers doing great things to improve our future. I’ve often wondered why technology isn’t more widely used to improve cities. It seems kind of stupid that we can chat face to face with friends on the other side of the world at any given moment, yet I have no idea when a free black cab is going to pass or when the traffic lights will change.

This is when I discovered Ross Atkin. I interviewed Ross - maker of Sight Lines - about his own vision for the future of mass personalisation.

As a designer who integrates technology into public spaces, and gives talks around the world on how we can better use technology in the city, Ross’s work is both inspiring and practical. Focusing his ideas on improving cities for the elderly and disabled, it’s clear his heart is in it for the right reasons.

Trained as an engineer, Atkin worked in design before getting involved in technology for cities. From this experience, his focus has always been on the small-scale – creating specific items for specific purposes, “by working from the ground up”, he told me “we’ll end up shaping an amazing future.”

Most of Ross’s work focuses on street design and using technology to help disabled people to navigate the city. He does things like create street lights which brighten for pedestrians with poor vision and has created an app which tells its user whether access routes are open. By following his ambition, his day-to-day work has branched out into a whole range of areas. He now creates a wide range of products, as well as advises companies and government bodies.

I had never given much thought before to how difficult it must be to move about the city as an elderly or disabled person. Ross explained to me the frustrations of people bumping into a temporary sign, or walking onto the road when there’s no way of knowing the pavement will end. I soon realised that for many people, the whole idea of trying to navigate the city – which changes every day – seemed pretty damn scary. My constant complains about bad bus timetables and traffic lights suddenly seemed pretty petty.

Chatting with Ross, it became clear to me that although his interests are broad, he’s mainly passionate about improving urban environments for people who need it most, “different people experience different things in cities which are inconvenient and annoying,” he told me, “I’m very interested in working with disabled and elderly people because the level of inconvenience they experience in cities is much higher. So, there is an amazing opportunity to make a big impact.”

With over half of the world’s population now living in cities, and with an ageing population, it’s easy to see just how big an impact this will have. The race for cities across the globe to become more beautiful and more ‘liveable’ has begun, and technology will no doubt play a huge role in the way this race folds out.

In addition to creating apps and responsive street furniture, one of Ross’s coolest technology projects is called ‘Sight Line’, which enables people with bad sight to learn all the details of construction sites through a transmitter, or app. Not only will the pedestrian quickly know how wide the construction site is, but they will know how long it will be there and even how to get around it.

“Construction works on footpaths is seriously hard for the visually impaired,” Ross told me, “if somebody can’t access the path that they normally take, and they have no idea how to get around the construction works, they can get completely stuck.”

The awesome thing about Sight Lines is that it taps into existing data already recorded by contractors, so there’s no extra management work needed. By using existing technology and information, Ross’s work is able to completely transform the way people interact with their surroundings. Pretty cool.

When I asked Ross how he imagined the future of cities, he told me that it would probably look something pretty similar to today. Slightly disappointed, I asked, “no changes at all?”

Ross explained, “I just don't really buy into the idea of having a ‘grand vision’ for how the city will look in the future. Instead, I’m focused on solving the problems that exist right now, with the technology we have today.” He imagines an incredible future with amazing improvements, but he doesn't think we’ll get there by drawing big plans. Instead, he thinks, we should focus more on making practical improvements to all the little things - one at a time.

With such simple, yet useful ideas, it was awesome to meet Ross who is at the forefront of creating products that will undoubtedly help to shape the future of our cities.

As part of MINI’s Future Shapers project, in the next few weeks I’ll have the opportunity to see how MINI is exploring its own vision of the future as part of its exhibition ‘BMW Group Future Experience", at the Roundhouse 17 – 26 June 2016. The exhibition will look at groundbreaking new technology that will affect how we live in 100 years. Visitors will be able to see a future MINI, a “Vision Vehicle”, that demonstrates applications of this new design and technology in an iconic car.

Visit MINI.co.uk for free tickets.

(And make sure you check out the full interview below!)

Why I like Brutalist architecture /

Brutalism seems to divide opinion like no other type of architecture. Between the 50s and 70s huge, grey, concrete buildings were built across cities around the world. While a lot of people hated their ‘inhuman’ and overbearing aesthetic, the architects designing them thought they were creating a new kind of utopia.

Until a few years ago, I knew nothing about this type of architecture. But it wasn’t long before I fell in love with taking photos at The Barbican Estate, and soon learned a bit about the movement.

Whether I love or hate the look of a particular brutalist building, I now really appreciate what it was trying to achieve. Now, every time I head off to a new city, I seek out these buildings and try to learn a bit about what they were trying to achieve in each place. From scanning the internet, it looks like other people love it too.

The term ‘brutalism’ comes from the French word ‘brut’, meaning ‘raw’. That’s exactly what these buildings are. So different from elegant design and detailing in the past, their designers used rough concrete with hard textures, and showed-off elements of the building that used to be hidden, like lift shafts.

The thing that I think is cool about brutalism is not the way it looks, but that it was designed with the best, optimistic intentions.

After the World War II, Europe was trying to rebuild its cities in a way that fixed a lot of its problems from the past, and Brutalism was all about trying to make buildings as cheap, functional and equal as possible. By making sure the building’s foundations were exposed, architects hoped that the ordinary could be seen as an art form, and in doing so - make them attractive to every person in society - whether rich or poor.

A key element of brutalism in London was the idea of creating ‘streets in the sky’, which would connect apartments blocks or offices. The idea was that neighbours could talk, kids could play and people could walk to work way above the fast-moving traffic below.

In the period of two decades, once low-lying urban areas were quickly transformed by towering concrete structures by architects and planners who envisioned a utopian city, where residents lived equally.

The ideas were cool, but in practice, it didn’t take long before the brutalism movement came to an end. It’s considered a social experiment, which didn’t really work. People soon realised that these buildings created strange ‘placeless’ spaces and restricted pedestrian movement through urban areas, which encouraged isolation and crime.

After harsh criticism for years, many of these buildings were demolished and some have been preserved. In London, my favourite surviving examples are Robin Hood Gardens, Balfron, Trellick Tower, and The Barbican.

The thing that I find super interesting about the Brutalist Movement, is how bold these planners and architects were: they saw a problem in society and they set out to find a solution for it through design. Sometimes I feel like society lacks some of that audacity these days. We have as serious housing shortage in London right now, and no one seems to be doing anything to fix it.

To me, this style of architecture represents a group of optimistic designers who were experimenting with a courageous idea - and that’s pretty cool.

Photos and film copyright Tom Oliver Payne.

The Commuter Journal: a review /

I love travel, cities, bikes and photography. My favourite magazine Huck does an amazing job of covering all of these things. The mag exposes the work of some of the world’s...

Read MoreCopenhagenize Bicycle Index 2015: the winners and the losers /

Bicycle revolution or urban fad? /

Cities across the world are seeing a dramatic increase in cycling. Is this a short lived fad, or are we witnessing the start of a revolution in urban transport?

The rise of the car in the 50s and 60s completely transformed cities – first across the USA, and then the world. Once centred around walkable shopping districts and train lines, cities began to spread into vast suburbs and homogenous landscapes.

Cars didn’t only change our cities, but they also changed our way of thinking. The car became a symbol of freedom, a symbol of maturity and a form of identity in the western world.

Today, we are seeing cities across the globe turn to alternative forms of mobility, and trains, trams and buses are back on the planning agenda in a big way. 60 years ago, one of the world’s most extensive tram networks (180 miles) was destroyed in Sydney, Australia, to make way for the private car. Today, the city is once again investing billions into a new light rail system that it hopes will relieve some of the city’s severe congestion.

We’re also seeing (re) investment into bicycle infrastructure in downtown districts across the globe. Over the last few years, cities like New York have constructed hundreds of miles of bike paths and bike share schemes are popping up in every corner of the globe – from Hangzhou’s ‘Public Bicycle’, to Paris’ Vélib’, to Montreal’s ‘Bixi’.

Bikes are also having a renewed surge of popularity. Portland hipsters are taking to the streets on fixies, east Londoners are dusting off vintage Raleighs and Sydney corporates are swapping golf clubs for lycra… As a result, the growth in cycling numbers has been immense in many cities worldwide. Italy has recently recorded that bike sales have outstripped car sales for the first time since World War II; the number of commuter cyclists in new York has doubled over the last five years; and for the first time in decades, a London borough (Hackney) has recorded that more people cycle to work (15%) than drive (12%).

Is all of this a revolution, or is it simply an urban fad?

The ‘bike boom’ of the United States saw similar trends in the late 60s and early 70s. Between ‘63 and ‘73 bike sales increased from 2.5 to 15 million, companies such as Union Carbide installed bike racks for employees and more than 50 cities across the country began planning bike paths with funding from the federal government. While there are many assumptions about why the American ‘bike boom’ ended, it’s likely that it had something to do with the end of the fuel crisis and recession.

Unlike America in the 70s, today we really are beginning to realise that our growth is unsustainable. We’re aware that we can no longer keep producing without recycling, we can no longer all own large homes, and we can no longer all drive to work – not only do our cars not all fit in our cities, but we are also running out of the very resource that drives them. There are simply too many of us. And yes, some argue that in our highly urbanised world, we could spread our wings by repopulating and revitalising rural areas. But not only do we rely on the economies of scale of cities to compete in the globalised world, but the ‘green’ countryside is also very ‘brown’. Those living in spacious rural areas generally have far greater environmental impacts than those in cities. As a result, we’re seeing transit-oriented housing developments, a move towards cleaner energy sources, urban congestion taxes and rising fuel prices. These are all putting pressure on drivers and making the move to two wheels seem slightly more practical.

Is the movement global? Not every city is adopting bike use in the same way, and some cities aren’t moving towards bikes at all. An array of factors will determine how, exactly, these changes are occurring. Some cities already have a deeply embedded bike culture (Copenhagen), some cities have stubborn politicians (Sydney), some cities are simply too hot (Phoenix), too cold (Ulan Bator) or too vast (Los Angeles). But across the globe we are beginning to witness a shift in the way we think about urban mobility.

The car will not simply disappear and bicycles will not suddenly take over our streets. But as we look for alternative solutions to our current transport woes, cycling is suddenly looking like a pretty smart option.

Rather than just a fad, I’d argue that today’s boom will be sticking about for a while. Just like the revolution of a wheel, we are perhaps, returning to where it all began.

A talk by Lord Richard Rogers: Architecture and the Compact City /

This is an awesome talk, particularly interesting for someone like myself who lives across Sydney and London. So much to take from this. I think most importantly are the Rogers' final principles for what he calls an 'urban renaissance'...

Read MoreMusic and architecture... Vito Acconci, the optimist! /

"Both music and architecture make a surrounding. They make an ambience. But also, both music and architecture allow you to do something else. Something else while listening to music..."

Read MoreIs there an urban creative crisis? /

Cities are not merely creative but capable of generating and nurturing hope, innovation and sense of possibility...

Read MoreSeven billion people, over half in cities /

Cities are not just buildings and roads sitting the surface of this earth, but they're living, moving, organic and real; they must change and evolve just as human beings do.

Read MoreHow we can design for human desire /

Have you ever noticed a dirt track through a public park or a group of people who meander across a street in seeming defiance of authority?

Well, that's because we, as humans, utilise something called 'desire lines'. Coined by French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, desire lines describe the human tendency of carving a path between two points (usually because the constructed path takes a circuitous route).

Across the globe urban authorities tend to try to control people's walking desires by erecting fences and walls. This illustrates nothing but a disrespect for human desire.

Instead, planners and designers should be acting to adjust urban infrastructure to appreciate the way in which humans utilise urban space.

The image above shows a terrific example from Gladesville in Sydney. Travelling from the city's north into the Inner West, one must traverse a number of waterways. For private cars, this journey is relatively direct and well-signed. For pedestrians and cyclists on the other hand, the journey is indirect and rather complex, leaving people to navigate multiple underpasses and complicated road-crossings. Not what you want on a hot Sydney summer day. As a result, pedestrians and cyclists have forged their own path which allows them to avoid a good 300m underpass walk. Instead of observing and redesigning the space to accommodate for the desires of people, the roads authority has continually tried to stop the movement of people by erecting fences at multiple sections along the path.

Is Sydney a city for people or a city for vehicles? It seems that the Roads and Maritime Services would prefer it to a place for cars (I guess it's all in the name, right?).

As cities move from being overly engineered and private vehicle-dominated, observing desire lines will act as an incredible tool in urban design, place making and urban management.

In the words of Mikael Colville-Andersen, "Instead of erecting fences to restrict them in the behaviour, they [Copenhagen Council] actually make it accessible for them and make it easy for them. Because people - at the end of the day - decide on where they want to go... This is the way forward in designing our cities for people". Check out his great little film below:

Episode 09 - Desire Lines - Top 10 Design Elements in Copenhagen's Bicycle Culture from Copenhagenize on Vimeo.

Feature image courtesy Adventures in Photography.

How micro-financing can help create sustainable cities /

Cities are experiencing rapid growth across the Global South. With this growth however, also comes economic disparity and environmental degradation. Can micro-finance offer a solution to these growing concerns?

One hundred years ago, just 2 out of 10 people lived in urban areas. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 5 out of 10. The number of residents in cities is now growing by about 60 million per year and is expected to increase from 3.4 billion in 2009 to 6.4 billion in 2050. Almost all of the urban population growth in the next 30 years will occur in cities of developing countries – much of which will be across Asia.

It’s estimated that Bangkok for example, will expand another 200 kilometres from its current centre over the next decade.

Rural to urban migration across Asia is occurring on a scale never seen before. Another 1.1 billion people will live in the continent’s cities over the next 20 years. It’s anticipated that in many places, entire cities will merge together to form urban corridors, or what some refer to as ‘megalopolis’ regions. It’s estimated that Bangkok for example, will expand another 200 kilometres from its current centre over the next decade.

With mass urbanisation has also come significant concern with regard to economics disparity and environmental sustainability.

From one perspective, rural to urban migration is thought to be helping to alleviate poverty by pushing more people into the middle class. Additionally, increased urban population density is seen to be ‘green’ because it lowers dependency on private vehicle use and increases resource efficiency. From another perspective however, mass urbanisation also causes a variety of problems across a range of geographic scales: socio-economic inequality, slums, sprawl, deforestation, air pollution, excessive waste and poor water management, to name a few. There is no ‘silver bullet’ for these problems.

While significant research is being conducted into how governments can best manage large-scale rural-urban migration, many troubles resulting from mass urbanisation are largely out of government control. One of which is access to finance. In order to gain a foothold in the city, new migrants require money to look for housing, initiate a business or find a job. With low levels of excess income and no permanent address, this is not as easy as walking down to the local bank branch and asking for a loan.

The inability to obtain capital can place new residents into financial traps. Burdened with huge overheads, people are forced to borrow and operate through the informal sector. While informality is not necessarily a bad thing (providing jobs, housing and networks where they may not normally exist), its unregulated nature can also lead to unethical and unsustainable business practices. In the longer term these practices can exacerbate poverty and environmental degradation.

Lendwithcare.org was launched in late 2010 as a branch of Care International, in association with The Cooperative. Allowing people to make small business loans to entrepreneurs in developing countries, and it gives people the opportunity to climb out of poverty.

Already active in Cambodia, Togo, Benin, The Philippines, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Ecuador, the programme has experienced particularly high growth in Asia where we’re seeing large scale rural to urban migration. To work with this growth Lendwithcare.org has recently also become operational in Pakistan.

The programme works with a number of partner microfinance institutions (MFIs) in the countries in which it operates. If the MFI is happy with an entrepreneur’s idea or business plan, they approve the proposal and provide the initial loan requested. Once the entrepreneur’s loan is fully funded, the money is transferred to the MFI to replace the initial loan already paid out to the entrepreneur.

The great thing about all of this is that microfinance is in and of itself “green”. Put simply, it promotes businesses that can be sustained indefinitely. When those living in poverty are given the opportunity to earn a living in a legitimate and sustainable manner, they have no need to become involved in unethical or unsustainable practices. Additionally, most organisations involved in microfinance such as Lendwithcare.org, hold sustainability as a precondition for awarding loans. Others may encourage greener businesses by offering lower interest rates to borrowers with sustainability-oriented plans.

Already programmes like Lendwithcare.org are having incredible impacts on the environment in places where it’s needed the most.

Here’s an example. Approximately 84% of people living in The Philippines depend on motorised tricycles for transport – 70% of which have polluting two-stroke engines. As you can imagine this is having a devastating impact on the environment as well as on the health of urban residents. While the local council of Mandaluyong City in Manila has recently enacted legislation requiring all tricycles to switch over to cleaner liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), this requires a significant (and often unaffordable expense) for tricycle taxi drivers.

This is where Lendwithcare.org comes in. Committing to local partner Seedfinance is now raising $25,000 in order to provide smaller loans of $500 to 50 motorized tricycle taxi drivers in Mandaluyong City so that they can pay for their vehicles to be switched over to LPG without crippling their livelihoods.

This highly ambitious project has the ability to alleviate poverty at the local scale, while ensuring that important urban sustainability targets can still be met across the region. By assisting ethical entrepreneurship, microfinance ensures that economic and environmental sustainability go hand in hand.

Writing once before on the innovative business models that are helping to create a more just and sustainable world, I’m quickly beginning to realise that the traditional corporate model is diminishing.

As urbanisation rates continue to soar across the globe we’re beginning to appreciate the incredible networks that are unfolding between the public, private and not-for-profit sectors. These networks are producing outcomes that promise to benefit more than just corporate shareholders.

Feature image by Tom Oliver Payne.

Remaking London: An Interview With Ben Campkin /

Ben Campkin is the Director of UCL’s cross-disciplinary Urban Laboratory and Senior Lecturer in Architectural History and Theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture. In his new book Remaking London, Campkin focuses on contemporary regeneration areas, places that have been key to the capital’s modern identity but that are now being drastically reconfigured. Rather than simply analysing these tensions in the current political climate, he discusses them in relation to the context of their historical urbanisation.

Read MoreMikael Colville-Andersen: teaching us the fundamentals of good urbanism /

Jane Jacobs reminded us of the city's most important element and inspired a generation of urbanists. Through a single photograph, Colville-Andersen has sparked a new movement that is helping to solve the greatest urban challenge of our time.

Jane Jacobs was revolutionary. By critiquing the modernist approach of twentieth century urban thinking, she taught us that traditional planning policies oppressed and rejected the single most important element of cities: people. Her ideas sparked decades of urban social movements, resulting in the preservation of inner city neighbourhoods across the globe. In the age of rationalism, she reminded us that cities are complex and chaotic. She reminded us that cities are human. Jane Jacobs (aka “The Crazy Dame”) inspired a generation of urbanists.

She reminded us that cities are human.

While Jacobs’ words continue to reverberate through history, this century we are faced with a new set of challenges. One in particular, dictates the way we govern, design and build urban spaces; it burdens our health care and kills our planet. Today’s greatest urban challenge is the car.

Our addiction to the car has made us crazy. We teach our children to fear the street and we fight wars to ensure we have reliable access to oil. Our obsession with the car controls just about every aspect of our urban lives. Like a drug however, it is destroying us from the inside out, not only is our atmosphere polluted and our streets congested, but every new road, car park and set of traffic lights makes our cities a little less livable. We have once again forgotten that cities are human.

Change however, is beginning to take place. We’re realising that there is a cleaner, more efficient and more human alternative to the car. Slowly but surely, we are now seeing the emergence of a global bicycle renaissance. This global movement can be traced back to a single photograph.

I started taking more photos of elegantly dressed commuters on bikes, and people kept reacting to them… after 6 months I thought I’d start a blog. It just exploded.

Back in 2006 Mikael Colville-Andersen was a film director. “I took a photo on my morning commute, which naturally involved bicycles… It wasn’t a great photo,” he told me, “it was just nice morning light”. A short time after uploading to Flickr, the photograph had received hundreds of hits and dozens of comments from around the world. “These comments started to appear from America like, ‘Dude! How does she ride a bike in a skirt?!’ So, I started taking more photos of elegantly dressed commuters on bikes, and people kept reacting to them,” he said, “after 6 months I thought I’d start a blog. It just exploded.”

At the time Mikael had no idea that Cycle Chic – as he later coined it – would become a global phenomenon. Nor did he know that it would spark an entire movement in new urban thinking. Just like Jacobs, Mikael was not trained in urban planning, but has become one of the most influential urbanists of our time.

It just so happens it was all by accident. “I didn’t realise these photos would be interesting to people,” he told me, “regular people, in regular clothes, using bikes as transport in the city… An entire generation of people all around the world had been told that cycling is sport and recreation. I was just a Copenhagener”.

Bicycles were once a common form of mobility in cities and towns around the world. Riding a bike wasn’t necessarily a sport or a sub-culture – it was simply a part of everyday life. The mass production of vehicles saw all of this change. The rise of the car after World War II completely transformed cities – first across the USA, and then across the world. Dense urban districts centred on transit hubs and commercial districts, spread into vast, car-dependant landscapes.

Unlike most of the world however, the rise of the car was short-lived in Denmark. As streets congested, air quality deteriorated and pedestrian fatalities mounted throughout the 60s and 70s, people took to the streets to demand equality for cyclists and pedestrians. In response, an extensive network of cycle paths was developed, traffic calming measures were implemented and people were encouraged to cycle. Today, riding a bike is once again part of everyday life: 37% of Copenhageners cycle to school or work. This figure stands at just 2% in Britain and 1% in North America.

After Cycle Chic and then Copenhagenize.com burst with internet traffic, Mikael decided to “give up film directing to see where this bike stuff was going”. His photographs had already sparked a bicycle buzz, and fashion labels were quickly jumping on the bandwagon. Fortunately however, the fad didn’t end there. In addition to online media, Mikael began promoting Copenhagen’s bicycle culture to urban planners and policy makers. The rest, it seems, is history.

Mikael could never have imagined that his 2006 Flickr image would become known as ‘the photo that launched a million bicycles

Just about every city in the world is now talking bikes. New York has recently rolled-out a massive bike share scheme to complement it’s new cycle paths, Hangzhou has launched the world’s largest bike share programme and the UK central government just commenced a multi-million pound cycling infrastructure scheme. The New York Times has even reported that we’re experiencing the “End of Car Culture”. Mikael could never have imagined that his 2006 Flickr image would become known as ‘the photo that launched a million bicycles’, as one journalist put it.

Sitting with Mikael at a café in central Copenhagen, we watched dozens of people passing on their bikes. Smiling at us as they passed, or stopping to chat with friends on the street, it became obvious to me that Mikael could envision cities of the future because he already lived in one. As Mary Embry from Copenhagenize Design Co. once said, “People work hard to make sure their cities are as user-friendly as Copenhagen… World-class cities want in on the cycling infrastructure and they look to Copenhagen for inspiration and guidance.” Copenhagen truly has become the model for livable cities.

At the café Mikael soon asked me, “you up for a ride on the Bullit?” as he looked over at his cargo bike parked on the street (#parkwhereyouwant). Standing at 6’2”, I awkwardly clambered into the front carrier. Conscious of the fact that my lanky legs were up by my ears, it didn’t take long before I was reminded where I was. In Copenhagen, you’re not judged on what bike you have, what ‘style’ you have, or how ridiculous you may look, as long as you’re on two wheels – anything goes.

Mikael took me around the city to show off some its most innovative bicycle infrastructure initiatives. First up was Dronning Louises Bro: the world’s busiest bicycle thoroughfare. Now, if someone took you to the busiest car thoroughfare in the world, you probably wouldn’t want to stay for long. It’s quite the opposite when people are riding bikes: this place had some serious energy.

A bridge where over 30,000 people come through on bikes each day makes for pretty great socialising and people-watching. So much so that the City even decided to widen the cycle paths to make ‘conversation lanes’. Bikes aren’t just great for transport: they’re also a brilliant place making tool. Unlike cars – Mikael reminded me – you can actually make eye contact with, and talk to people when they’re riding a bike.

Cruising around the city to check out Copenhagen’s bicycle footstands, commuter counters, and of course, the new Cycle Superhighways, I was then shown where the City had installed cycle paths to complement commuter’s desire lines. First promoted by William H Whyte back in the 60s, the team at Copenhagenize is now at the forefront of utilising observational techniquesfor pedestrian and cycle planning. Just like Jane Jacobs, Mikael is working hard to make cities less rational and more organic.

Working closely with media, architects, planners and policy makers around the world, Mikael is continually exposed to the ideas and projects that are reshaping cities. But to him, there’s only one city that is really doing it right. Copenhagen has not become complacent as the world’s greatest cycling city, it’s continually striving to increase bicycle modal share and improve the experience of cyclists. Mikael’s goal is to communicate this culture to the rest of us… I guess ‘Copenhagenize’ says it all.

Through a single photo back in 2006 Mikael has showcased a place where cars no longer dominate. And now, city-by-city, a new urban social movement is taking shape. We are beginning to mend the urban fabric that the car has torn to shreds. Just like “The Crazy Dame”, Colville-Andersen has reminded us that cities are human. By inspiring a generation of urbanists, he’s also helping to solve the greatest urban challenge of our time.

Check out this article posted on the Urban Times here.

All photos/text by Tom Oliver Payne.

How can we make ugly freeways more attractive? /

Friend of mine Rashiq Fataar at Future cape Town has written a really awesome article titled 'The Spaces Below' - all about how we can improve the spaces underneath freeways.

Read MoreIntroduction to Next-Gen Cities feature series /

We live in a new urban era. Not only do more people now live in cities than rural areas, but urban populations in the developing world are expected to more than double from 2.5 billion in 2009 to nearly 5.2 billion in 2050.

Urban populations in the developing world are expected to more than double from 2.5 billion in 2009 to nearly 5.2 billion in 2050

With this tremendous growth, cities are taking on new meaning; they are the centres of cultural diffusion, financial boom and bust, opportunity, prosperity and, as we have recently seen, solidarity.

Arguably, cities have surpassed the nation-state as key economic units and global organising nodes. With this, we have entered a new age of city competition as each fight for world city status, the largest events or the most important businesses. The current urban era is like nothing this planet has ever seen before.

The governance mechanisms and processes that manage our cities have been unable to cope with such change. Traditional ways of thinking about formality, traffic engineering, property development and architecture are quickly being overturned by a new urbanist movement; a movement that places the importance back on the human scale.

We are seeing a movement away from traditional zoning methods, egotistic architecture and car domination. Slowly but surely, we are also seeing the demise of the greedy downtown property developer. Perhaps if anything, the GFC has helped to spur this progress.

With this new wave of thinking, we are seeing a new wave of professionals including planners, architects, engineers, politicians, scholars and activists, who are quickly transforming the cities in which we live. Around the world, progressive thinkers are achieving amazing things. Whether its bridging the rich and poor housing gap, getting cycling on the infrastructure agenda, designing creating youth spaces or chair-bombing a local park, we are seeing rapid urban changes around the world.

This series for the Urban Times will hone in on cities across the globe to speak with the next generation of urban professionals who are particularly innovative in they way that they think. City-by-city, this series will take you on a journey across the globe to find give you an insight into the future of the urban.

I'll keep you up to date on the article numero uno.

Can you imagine life without light? /

Life as we know it would be very different without artificial light. By recognising the evolution of urban illumination in the two cities of London and Nairobi (where I went on a recent trip), we can understand how and why we've become so energy dependent. This comparison also reveals that, perhaps now more than ever, it's time to embrace new technologies.

Light is a form of energy. Simply, it’s a type of electromagnetic radiation that can be detected by the eye. This form of energy completely dictates our human existence. We in the ‘West’ have become very dependent on artificial light; without it, life would be very different. Yet we take light for granted. The hundreds of years that it’s taken to develop lighting technology for our homes, transport systems, streets and personal devices rarely cross our minds. For most of us, light is as simple as a flick of a switch.

This hasn’t always been the case. Civilizations across the globe were once subjected to the vulnerabilities of nightfall. In fact, it wasn’t very long ago. It’s only been over the last 100 years that cities have implemented electric lighting grids to power homes and streets. This development however, has not been global.

To imagine the darkness that continues to engulf cities and towns across Africa, I’ll first take you back in time to look at the journey that London has taken to become “the great city of the midnight sun”.

“Ye might say… that we’re ladin’ an artyficyal life, but, by Hivins, ye might as well tell me I ought to be paradin’ up and down a hillside with a suit iv skins… an’ livin’ in a cave as to make me believe I ought to get along without… ilictirc lights”

– Mr Dooley, 1906 (The City as a Summer Resort)

London was once a very dark place and unsafe place (yep, probably even more so than now). While living room fires and other illuminants, such as oil lamps and cannels, were used for special purposes, the only means for continuous lighting from the middle ages until the end of the 18th century was the candle.

A “night walker” was not only regarded with suspicion, but any unauthorized person caught roaming the streets after 9pm was arrested by the police. Over the course of the next 300 years, the city’s laws were continuously adjusted to ensure strict specifications for the use of lanterns to correspond with moonlight at different times of the year. Moving into the 18th Century, London saw the development of more permanent gas lamps as demand for lighting continued to increase.

There were three major reasons for increased demand in street lightingduring the early 1800s. Firstly, night-work and leisure continued to increase. Secondly, street lighting enabled those in rich neighbourhoods to contrast themselves from the poor. Thirdly, and perhaps the most obvious reason, was for safety.

One Londoner, Frederick Howe, wrote that street lights “guarded persons and property from violence and depredation… Every improved mode to street lighting the public streets is an auxiliary to protective justice”. The development of the electricity grid in the 1890s saw the delivery of widespread public lighting across the city.

With the evolution of new technology, London not only saw a transformation of the city, but it saw a transformation of the lives within it. Living in the ‘Western’ cities, it is easy to forget the contributions that the evolution of light has made to modern urban society. That is, until we experience life without light today.

In other parts of the world however, darkness is the norm. At the same time as electric lighting was being delivered on a large scale across London, the city of Nairobi was only just being founded.

In 2003, both London and North East America experienced major blackouts, impacting half a million and almost 50 million respectively. In both cases, major urban centres came to a standstill and our extremely vulnerable reliance on modern lighting was revealed.

In other parts of the world however, darkness is the norm. At the same time as electric lighting was being delivered on a large scale across London, the city of Nairobi was only just being founded. Today, as one of the most prominent political and financial centres on the African continent, it is a city of deep contrasts. While most of Nairobi stands relatively ‘developed’ (with widespread connection to the electricity grid), a third of its population live in informal settlements – remaining off the electricity grid.

On a recent trip to the city, I was able to visit two major slums to talk with locals about their living experiences. Far from the glum scenarios that are often portrayed in the media, these exciting neighbourhoods seemed to be thriving both culturally and economically. However, two major infrastructure issues were clear; water and lighting. While some residents have chosen to illegally hook up electricity from surrounding grids, this expensive and dangerous process (with local gangs profiting from the procedure) is generally unaffordable for Nairobi’s two-million or more slum dwellers.

Upon a visit to the Mathare slum Community Light Centre, I was fortunate enough to speak with a young lady from World Coaches who had spent her childhood playing football in the neighbourhood. Martha explained to me that Mathare had a highly organised football league comprised of 16 zones across the slum district (another realisation that these informal settlements are far from the messy, disorganised places that I once imagined). She told me:

“I grew up a Tom-boy… I starting playing football when I was 12, but my Mum didn’t like it. She told me it was a boy’s game. When I was young, we couldn’t play in the dark, we went home… there was always a danger traveling in the dark. I didn’t feel threatened though, I had nothing to lose. But it was unsafe. I know it was unsafe. I feel it now when I visit.”

Asking her about the benefits that the new solar-powered Light Centre will bring to Mathare, I sensed the excitement that she felt for the transformation of her old community. To me, it was a sudden realisation of the extent to which I took lighting for granted in my own neighbourhood. Martha explained:

“These lights are not only helping football… It’s helping young people in terms of security… not only security… shops shut early because it is dark. Even if shops can stay open just one more hour, it will have benefits to the local economies. I’m telling you, things will change”.

Thinking about the strict rules and regulations that once dictated the use of lighting across London, I wondered about the spatial tensions that may arise from only a partial delivery of public lighting within Nairobi slums. I decided to ask Martha. Embarrassingly, it was a stupid question:

“There will be no tensions… These communities are well organised and can take care of themselves. They know the benefits and will set up schedules when they need to.”

Continually underestimating the power of communal governance in Kenya’s slums, I was once again reminded of the amazing capability of local residents to share resources. Her statements also confirmed to me that when it comes to lighting and water infrastructure – every little bit helps.

The concept of light has strikingly different meanings in London and the slums of Nairobi. In the slums, light is seen as a wonderful asset that has the ability to provide new opportunities in safety, education, health and sports. In the UK, on the other hand, light is an element of everyday life that’s generally taken for granted. In a sense, the trip to the slums of Nairobi seemed a little like stepping back into 19th Century London.

On the other hand however, travelling to the slums of Nairobi was also like glancing into the future. With some of the planet’s highest levels of annual sunlight, and without the need to retrofit pre-existing infrastructure, some of Africa’s poorest, yet most resourceful neighbourhoods are rapidly advancing in the solar-powered lighting revolution.

While the implementation of more efficient LED-lighting is makingprogress in larger, ‘developed’ cities, such progress remains slow. As authorities drag their feet on climate change policy, urban infrastructure generally remains unsustainable and incredibly energy-inefficient.

Due to advancements in LED technology over the last decade, lighting has made incredible progress in efficiency and functionality. These improvements have the ability to play a major role in curbing energy usage, and human-induced climate change as a result.

Perhaps now, more than ever, cities like London should be paying attention to the progression of lighting technology. The slums of Nairobi not only provide a history lesson on life without light, but also provide examples of highly advanced, sustainable urban illumination.

Why bike helmets shouldn't be compulsory /

Decades of car dominance have made our streets congested, polluted and ugly. While some cities are now quickly embracing the bike, others have been slow. Helmet campaigns and legislation have been major obstructions to change. To get people moving on two wheels we must finally abandon our 'culture of fear'.

Read More