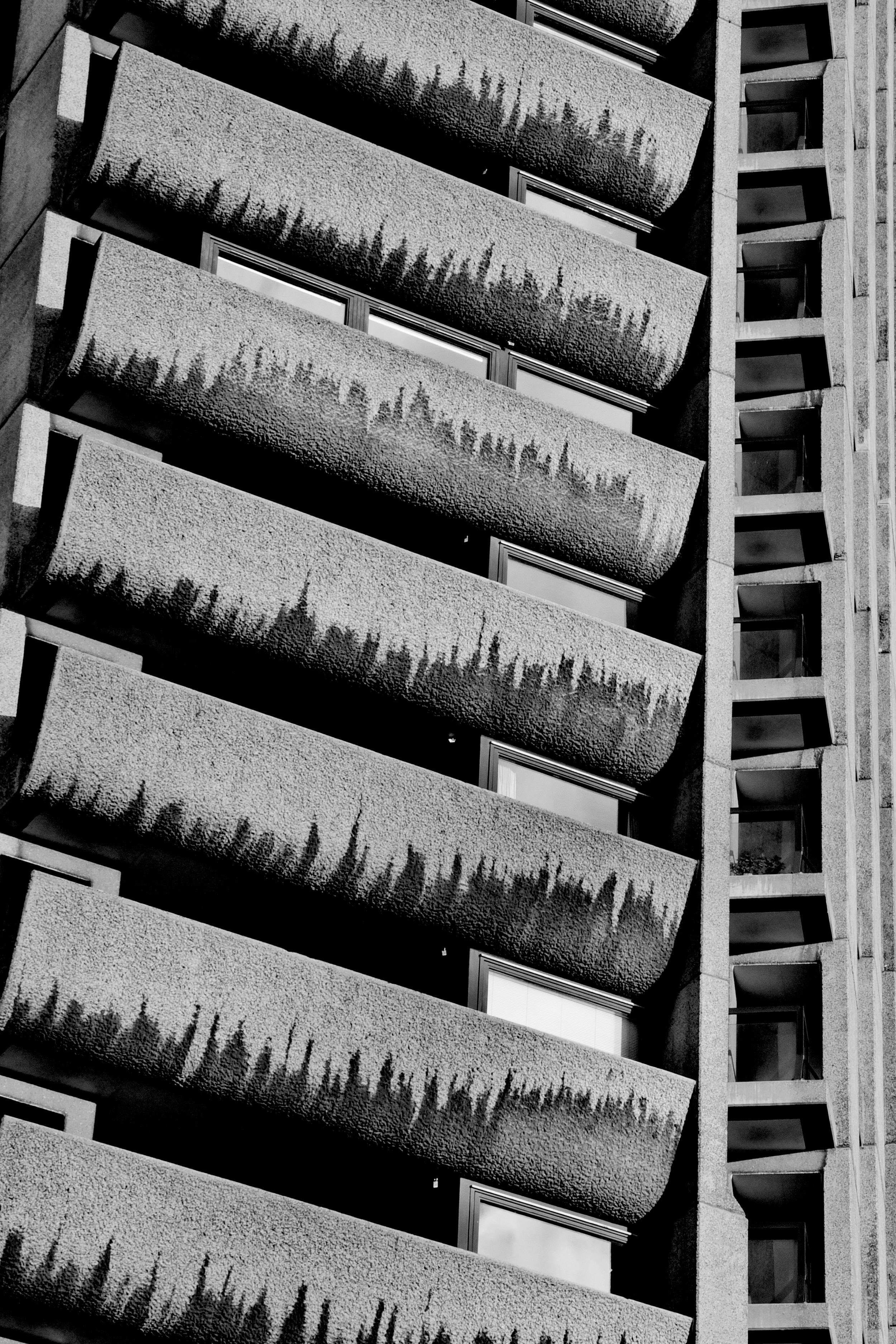

"The late 20th century was a unique period in architectural history in which buildings where designed to serve a social purpose. Brutalist buildings used the most basic material to keep costs down, and were most commonly built to house low-income residents or institutions.

Unlike 18th-century houses, their importance is about historic interest, rather than an aesthetic interest. Sirius, just like Trellick, Balfron and the Barbican in London, illustrates important aspects of the nation's social and cultural history."

Last week I had an opinion piece published in the Sydney Morning Herald on brutalist architecture in Sydney and London. You can read the full article here.

Photo by Jessica Hromas via SMH

Blog

Sydney Metro brought to life with stunning public art works