Brutalism seems to divide opinion like no other type of architecture. Between the 50s and 70s huge, grey, concrete buildings were built across cities around the world. While a lot of people hated their ‘inhuman’ and overbearing aesthetic, the architects designing them thought they were creating a new kind of utopia.

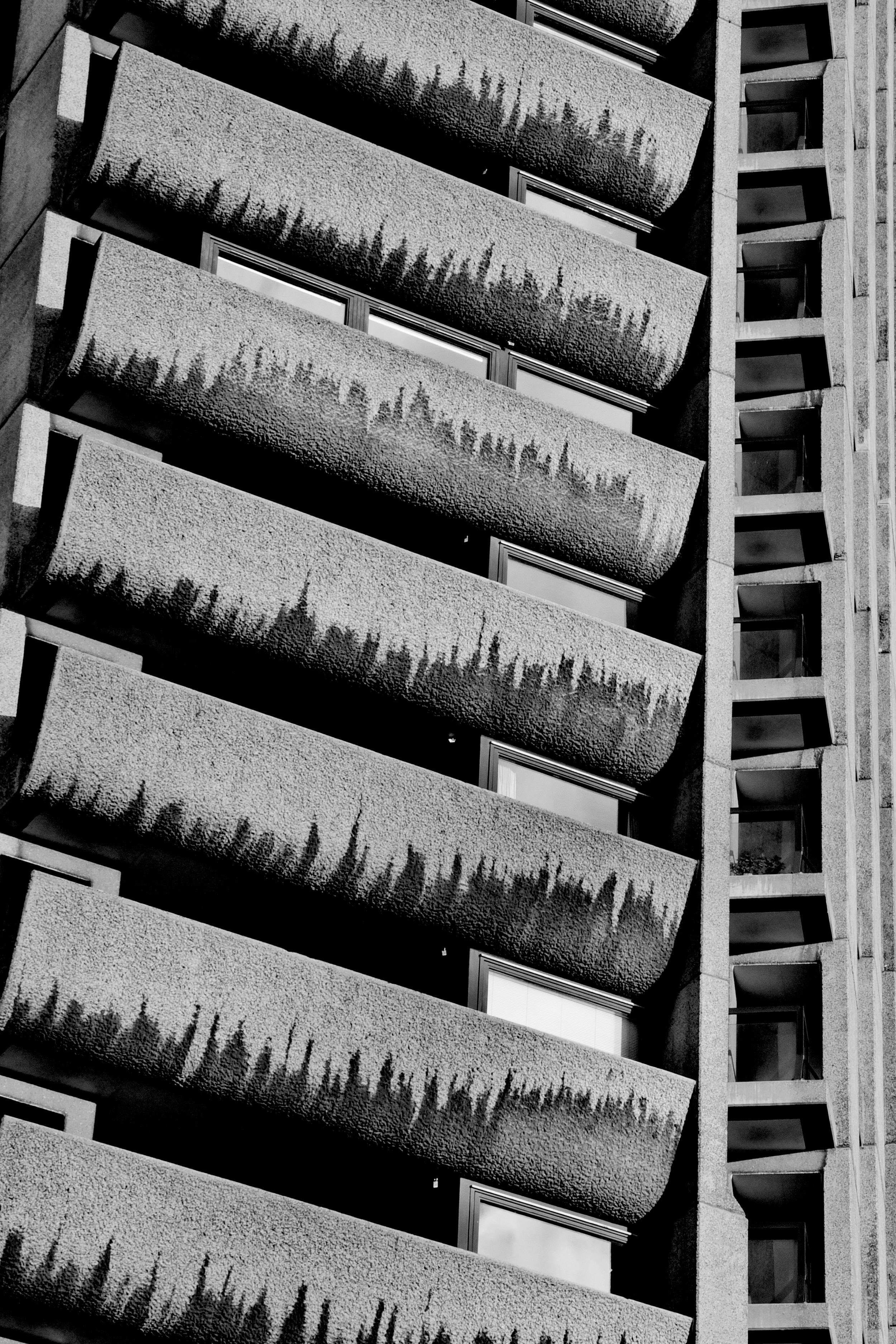

Until a few years ago, I knew nothing about this type of architecture. But it wasn’t long before I fell in love with taking photos at The Barbican Estate, and soon learned a bit about the movement.

Whether I love or hate the look of a particular brutalist building, I now really appreciate what it was trying to achieve. Now, every time I head off to a new city, I seek out these buildings and try to learn a bit about what they were trying to achieve in each place. From scanning the internet, it looks like other people love it too.

The term ‘brutalism’ comes from the French word ‘brut’, meaning ‘raw’. That’s exactly what these buildings are. So different from elegant design and detailing in the past, their designers used rough concrete with hard textures, and showed-off elements of the building that used to be hidden, like lift shafts.

The thing that I think is cool about brutalism is not the way it looks, but that it was designed with the best, optimistic intentions.

After the World War II, Europe was trying to rebuild its cities in a way that fixed a lot of its problems from the past, and Brutalism was all about trying to make buildings as cheap, functional and equal as possible. By making sure the building’s foundations were exposed, architects hoped that the ordinary could be seen as an art form, and in doing so - make them attractive to every person in society - whether rich or poor.

A key element of brutalism in London was the idea of creating ‘streets in the sky’, which would connect apartments blocks or offices. The idea was that neighbours could talk, kids could play and people could walk to work way above the fast-moving traffic below.

In the period of two decades, once low-lying urban areas were quickly transformed by towering concrete structures by architects and planners who envisioned a utopian city, where residents lived equally.

The ideas were cool, but in practice, it didn’t take long before the brutalism movement came to an end. It’s considered a social experiment, which didn’t really work. People soon realised that these buildings created strange ‘placeless’ spaces and restricted pedestrian movement through urban areas, which encouraged isolation and crime.

After harsh criticism for years, many of these buildings were demolished and some have been preserved. In London, my favourite surviving examples are Robin Hood Gardens, Balfron, Trellick Tower, and The Barbican.

The thing that I find super interesting about the Brutalist Movement, is how bold these planners and architects were: they saw a problem in society and they set out to find a solution for it through design. Sometimes I feel like society lacks some of that audacity these days. We have as serious housing shortage in London right now, and no one seems to be doing anything to fix it.

To me, this style of architecture represents a group of optimistic designers who were experimenting with a courageous idea - and that’s pretty cool.

Photos and film copyright Tom Oliver Payne.